Shooting at West Point, 1876

An 1876 shooting by a West Point sentry angered the local community and cost a carriage driver his life.

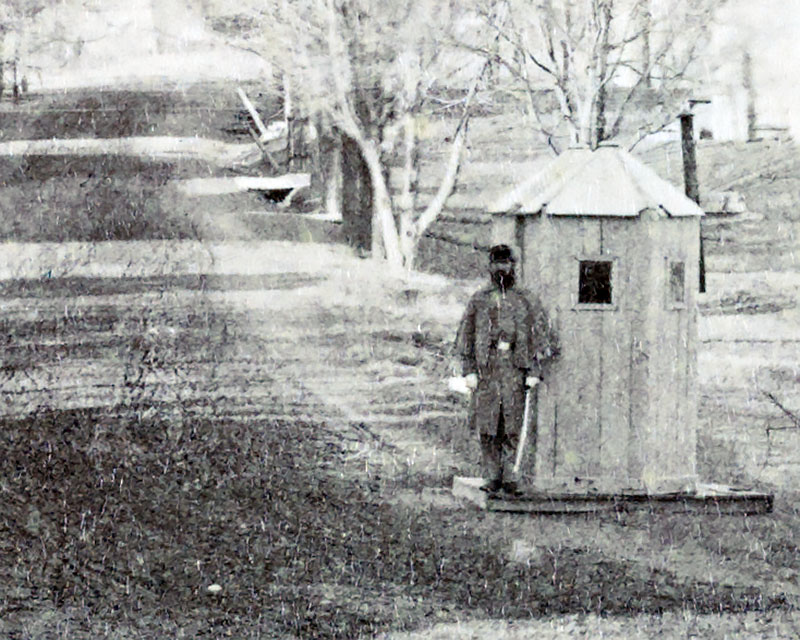

A West Point sentry in the early 1870s. It is not known if this is the site of the incident recounted here. Source: USMA Archives. Photo by Pittman.

On the night of September 8, 1876, Private John L. Rothelin, a German-born soldier stationed at West Point, was the sentry at the Post's southern gate. The location was likely the dark stretch of road a few hundred yards south of today's Mahan Hall. Rothelin heard a carriage approaching and yelled, "Who comes there?" The driver, who was returning to Buttermilk Falls (Highland Falls) from the Academy, called back, "A friend." Because of the darkness, Rothelin could not confirm the driver's identity, so he decided to let the driver approach into the light from the gas lamps at the guardhouse. It appears that the driver, William Porter, a.k.a. Washington Putnam, failed to stop, or possibly stopped and then started again. Rothelin again ordered the carriage driver to stop (the reason is uncertain) and when he did not, the soldier charged forward with his bayonet, which got stuck in the wheel. When he tried to remove it, the rifle, which was allegedly half-cocked, fired and hit Porter in the hip. The round was removed, but Porter died several days later from lockjaw.

A coroner's inquest was held about two weeks after the shooting. Rothelin recounted his version of the story. A Second Lieutenant, Henry L. Harris, USMA Class of 1869, testified that while the sentry's duty was to stop the halt the carriage, it was not expected that shots would be fired if a person refused to stop. Harris seems to have stated that he felt charges should be filed. The inquest jury concluded that Porter's death by lockjaw was Rothelin's fault, and issued a warrant for his arrest. Despite anger from the local community, military authorities refused to turn over the soldier until they had permission from Washington. Eventually, Rothelin was turned over.

From this point, the story is a bit unclear. In August of 1876, there is mention that the case was under investigation by a U.S. Grand Jury and that Rothelin was released on his own recognizance and returned to duty at West Point. Enlistment records indicate that he was court-martialed and discharged from duty at Willett's Point (later Fort Totten) on December 8, 1876. Sometimes a rifle does "go off half-cocked" with dire consequences.

Selected Sources:

"A West Point Guard's Fatal Mistake." Harrisburg Telegraph. July 25, 1876.

"An Over-Zealous Sentry." The Times (Philadelphia). July 27, 1876.

"Current Events." The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 11, 1876.

"Orange County Court." The Evening Gazette (Port Jervis, NY). September 30, 1876.

"Release of the West Point Sentry." Evening Star. August 11, 1876.

"The Shooting at West Point." The New York Times. July 26, 1876.

Central Area, 1870s

A look at a West Point photo from the 1870s.

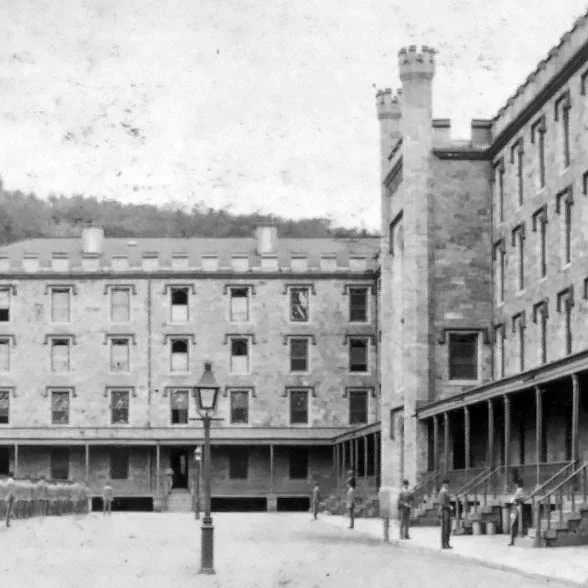

Today, let's take a look at a photo of Central Area from the 1870s. The barracks on the right and straight ahead are the Cadet Barracks (later Central Barracks) built in 1851 (although maybe not all at once). The configuration shown here lasted until 1882 when the shorter wing was extended by 105 feet. The style of the building is Gothic because of the castellated roofline, arched sallyports, and dripstones over the windows (among other details). Various sources call the style "Tudor Gothic", "Military Gothic", or "Elizabethian". It was likely designed by Superintendent Richard Delafield and matched the style of the Old Library and the Ordnance Compound (now the Firstie Club).

Cadet Barracks, circa 1875-1880. Source: New York Public Library.

As pictured, the Barracks had 10 divisions, each division consisting of a stairwell with rooms off of landings on each floor. There were no lateral hallways connecting the divisions. Eight divisions were in the long section (on the right in the photo) and two in the shorter wing that faces the camera. The 1st Division is the only one that survives (now containing Nininger Hall). The rooms in the shorter wing were often occupied by tactical officers or younger faculty members. The Barracks also had some offices, "light" prison rooms for cadets in trouble, and storerooms. At the time of this photo, there seems to have been no toilets in the building. Urinals and "water closets" were in a building across the Area (out of view on the left side of the photo).

The building on the far left of the photo is described in the 1880s as the Cadet Quartermaster's Department Store. It was three stories and constructed of brick. It contained a tailor shop, a shoe shop, and storerooms. The appearance of the building helps us date the photo. It was built in 1874 but the roof was altered to a mansard roof in 1880, meaning this photo was likely taken sometime between 1874 and 1880. In the photo below of the Old Gymnasium, you can see a sliver of the Cadet Quartermaster's Department Store with the mansard roof behind the gym on the left side of the photo.

Old Gymnasium with Cadet Quartermaster's Department Store in the rear. Source: NYHS

West Point Style, Part 1

West Point's got style! Architectural style. As people visit the Academy for football and foliage season, I thought it would be fun to do a series on West Point's many architectural styles. Today, let's look at one of the oldest styles at West Point, Federal.

The Federal Period lasted from about 1780 to 1820 and represented a further development of the Georgian architectural style popular during the Colonial period. Federal houses tend to be side-gabled, two-room-deep, simple structures with features inspired by Roman architecture. Many Americans refer to Federal houses as "Colonial" even though most were built after our independence. At West Point, the Federal style is seen primarily in surviving houses on the Plain and along Professor's Row. The Superintendent's House, the Commandant's House, and the three double-quarters on Professor's Row are all considered Federal homes.

Federal details on Quarters 100, West Point, New York. Photo ©2016 ExecutionHollow.com

On the annotated photo of the Supe's House, built in 1819-1820, many typical Federal details are evident:

- A semicircular fanlight over the front door is a very common Federal details. Look for it if your town was settled before 1840.

- The house is side-gabled. This is the most common roof configuration for Federal homes. Notice as well that the roof does not extend over the side walls. This is a tell-tale sign of an old building.

- The windows are symmetrical around the front door and are five in number on the second floor. Three- and seven-ranked configurations are also seen, such as on the Commandant's House (3-ranked). Also, the windows on the Supe's House have double-hung sashes, meaning the top and bottom sections of the windows open. The six panes in each window are common in Federal houses.

- Along the roofline, in the cornice, there are small tooth-like decorations called dentils. When at West Point, look for dentils on the Supe's House and the Professor's Row houses. The Commandant's House does not have dentils, suggesting it was built to be a simpler house than the Supe's. It also lacks a semicircular fanlight over the door. The houses on Professor's Row have dentils.

- The porch and additions on the Supe's House are not original. The porch is not Federal in style.

The Academy, built 1815. From Boynton, E, History of West Point, New York: Van Nostrand, 1863.

While the Federal architecture remaining at West Point is limited to houses, there was a time when many of the institutional buildings also had Federal characteristics. For example, look at this drawing of the 1815 Academy building. The semicircular fanlight and other details reveal a Federal style that would have meshed well with the Superintendent's House across the Plain, built just a few years later. Early barracks buildings also had Federal characteristics.

Next in this occasional series, we'll look at what happens when Ancient Greece and Rome became more prominent in American architecture.

The Great West Point Elevator

In 1903, West Point planned to build one of the coolest elevators ever.

At the turn of the 20th Century, West Point decided it needed to expand. Having erected individual buildings as needed for a half-century, the campus required not only new and larger buildings, it cried out for a cohesive design. In 1903, the Academy held a national competitive search to solicit bids. The competition was discussed in the newspapers and closely monitored by the public. Most of the leading architectural firms sent proposals. The winning firm was Boston's Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson. Their buildings, including the Cadet Chapel, the Administration Building (Taylor Hall), and the Riding Hall (Thayer Hall), are now synonymous with West Point's landscape.

But Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson also proposed numerous buildings that were never built because of budgetary restraints. Today, let's talk about what might have been the coolest elevator ever built. In the first decade of the 1900s, nearly all West Point visitors arrived at what is now known as the South Dock. Both the West Shore Railroad and numerous steamboats stopped here. Tourism was popular and in the summer the visitors were many.

The South Dock presented a problem that any West Point visitor or resident still deals with, namely a tough climb uphill to the main buildings around the Plain. For decades, carriages helped visitors get to the Hotel on Trophy Point from the dock, but Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson proposed building an elevator to take passengers to the flat level now occupied by Thayer Road. From the top of the elevator, visitors would have been facing directly uphill looking at a new hotel that would replace the then 80-year old one on the Plain. In the end, the Government decided that these projects were too expensive and were scrapped.

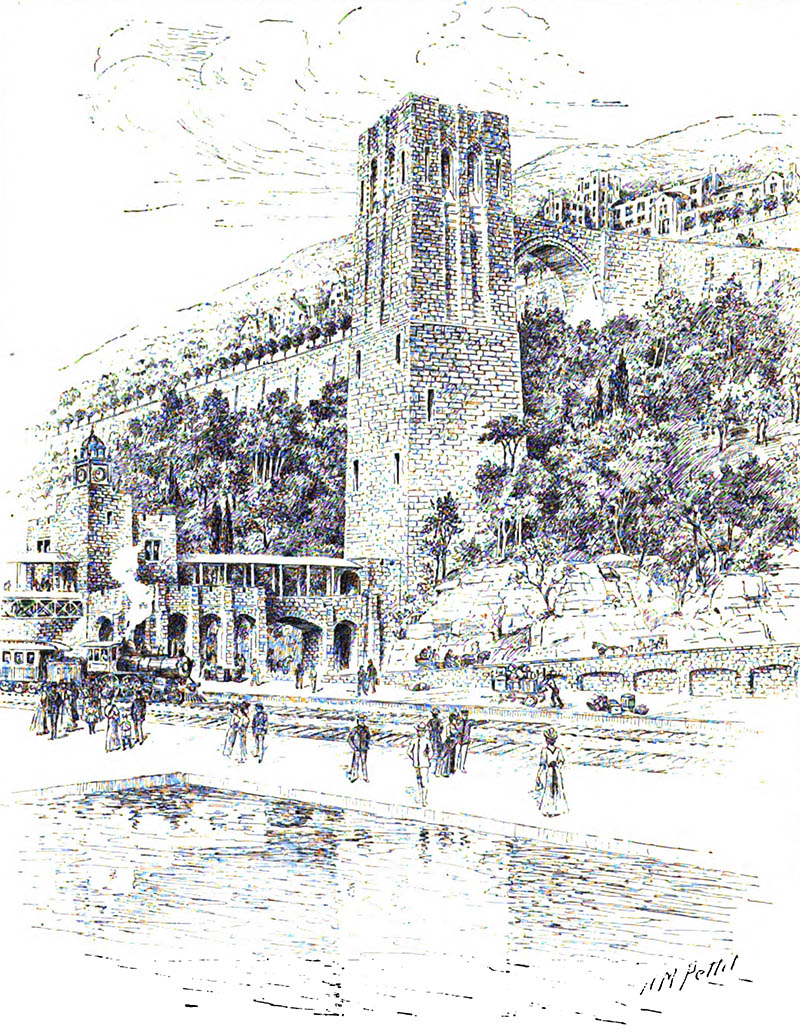

Below is a crop of a Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson plan showing the location of the elevator and hotel that were never built. Below the map I've posted two renderings of the elevator. The first is from 1903 and the second was published in 1908.

A 1903 plan by Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson showing the location of the never-built elevator connecting the dock to the elevation of the Plain. A proposed hotel on the hill was also never realized.

A rendering of the proposed West Point elevator from 1903.

A 1908 rendering of the elevator showing a connecting passageway from the station and dock with a clock tower. Notice the bridge connecting the top to the road.

West Point Academics, 1832

What was West Point's academic program like in the 1830s?

With West Point classes starting again, let's take a brief look back at the Academy curriculum in the old days. Specifically, let's look at 1832. In that year, the subject areas of the course of study were:

This is the Academy building, built 1815-1816. Some classes were held here, as well as religious services. It burned down in 1838.

Infantry tactics and military policing: Drill, how to maneuver, light infantry techniques, etc.

Mathematics: Algebra, geometry, trigonometry, mensuration, including surveying, perspective, and some aspects of calculus.

French: Reading, pronunciation, and translation.

Drawing: The human figure, landscapes in pencil and ink, and topographical sketching.

Natural & Experimental Philosophy: Statics and dynamics, hydrostatics and hydrodynamics (including electricity, magnetism, and light), and astronomy,

Chemistry and Mineralogy: Chemical philosophy, the application of chemistry to agriculture and industry, mineralogy, and geology.

Artillery: Nomenclature, gunnery, and pyrotechny., which included the making of cartridges for pistols, muskets, howitzers, cannons, etc. as well as rockets, "fire balls" and other explosives.

Engineering and the Science of War:

- Civil Engineering: Materials, architecture, construction, canal building, railroads, and harbor fortifications.

- Field Fortifications: Including bridge building.

- Permanent Fortifications: Constructing, defending, and attacking fortresses.

- Science of War: Composition and organization of Armies, orders of battle, strategy, and campaign planning.

Rhetoric, and Moral and Political Science: Grammar, philosophy, morality, ethics, civil society, civil rights, forms of government, U.S. government, and the law of nations.

The Use of the Sword: Small sword, broadsword, and sword exercises for cavalry.

The breakdown by year was:

1st Year (Plebes; 4th Class): Duties of a private; French; Algebra; Geometry; Trigonometry; and, measuring planes and solids.

2nd Year (Yearlings; 3rd Class): Duties of a Corporal; Running a Company; Artillery part 1; French; Mathematics; and, Drawing, part 1.

3rd Year (Cows; 2nd Class): Battalion operations; Duties of a Sergeant; Artillery, part 2; Drawing, part 2; Natural Philosophy; and, Chemistry.

4th Year (Firsties; 1st Class): Maneuvering; Duties of Orderly Sergeants and Commissioned Officers; Artillery, part 3; Mineralogy; Geology; Engineering and the Science of War; Rhetoric; Moral and Political Science; and, use of the sword.

Could you handle it?

Source:

Regulations of the U.S. Military Academy, at West Point. New York: J & J Harper, 1832.

Stay out of Philly

The ill-fated Cadet March to Philadelphia in 1820...

In West Point's early days, the Corps would often take a long march in the summer to practice the fundamentals of overland movement and to experience camp life. It also provided an opportunity for the Academy to practice public relations and put on a show for the towns through which the cadets marched.

William J. Worth, shown here during the Mexican-American War, was Commandant of Cadets in 1820. Source: Yale University Library (Public Domain)

In August of 1820, the march destination was Philadelphia. But, public health got in the way. After days of marching in the rain, the Corps made it to Bristol, PA, about 20 miles north of Philly on the Delaware River, but were denied entry to the city by Philadelphia officials. The reason? Malignant fever! We now know this was Yellow Fever, a recurring scourge for early American cities. In 1793, Philadelphia lost 5,000 people to the disease. So naturally, the Board of Health in 1820 was cautious about visitors to the mosquito-infested city.

What to do? An Army officer needs to be resourceful, and Major William Worth, the Commandant and a combat veteran of the War of 1812, was just that. The cadets put on a parade at Bristol to guests from the surrounding countryside and from Burlington across the river. The maneuvers were a hit and were described as "gay and animating."

The next day, they were invited by citizens of Philly to come to the outskirts of the city. They were given use of a steamboat and headed south to Bridesburg (aka "Point-No-Point"), now one of the northernmost parts of Philly. The boat was given a salute as it neared. The Corps was then escorted to view the newly built (1816) Frankford Arsenal. Later, they were escorted by local volunteer companies to Mantua, a neighborhood in West Philadelphia near the current Philadelphia Zoo. The next day there were religious services and a dinner was arranged for the cadets. The following day, Major Worth started the Corps marching north to ensure that the young men were back before the 1st of September for classes.

In the end, the Corps never was allowed to visit downtown Philadelphia due to the "state of alarm" there, but the safety of the cadets was paramount.

Philadelphia, 1819 with key places noted. Source: NARA

Sources:

"The Board of Health of Philadelphia...," Providence Patriot, Columbian Phenix (Providence, RI), August 23, 1820 (68).

"The Cadets," The Philadelphia Gazette, as quoted i The National Advocate, for the Country, August 25, 1820 (705).

"Major Worth," The Philadelphia Gazette, as quoted i The National Advocate, for the Country, August 04, 1820 (699).

Grave of Ransom Huntoon

A photo essay of the gravestone of Cadet Ransom Huntoon, USMA Class of 1834.

Ransom Huntoon was a member of the West Point Class of 1834 from New Hampshire. He fell ill in early 1834 and passed away on February 18th of that year in Unity, New Hampshire. He is buried in the East Unity Cemetery. His gravestone reads,

Ransom Huntoon, a Lieut. in the corps of Cadets, attached to the United State's Military Academy: West-Point, Died, Feb. 18, 1834, Æ23.

The symbols on Cadet Huntoon's gravestone are interesting. On the top (the tympanum) is a weeping willow draping an urn, a common 19th-century headstone symbol. Some scholars connect the willow with the Greek goddess of the underworld Persephone. The period in which Huntoon died was the height of the Greek Revival period in America. Below the willow and urn are an artillery piece and cannonballs representing his military career.

Below are three photos of the gravestone.

Grave of Ransom Huntoon, 2016. Photo by Author.

Detail of the weeping willow and urn on the tympanum. Photo by Author.

Gravestone of Ransom Huntoon, 2016. Photo by Author.

Gun Carriage Accident, 1902

A short tale of a gun carriage accident at West Point in 1902.

I love the small side stories of West Point history. Items that are left out of the broad overviews that cover Grant, Pershing, and Ike. Today's article is about a gun carriage accident in July of 1902. The main player in the story is Captain Edwin St. J. Greble, son of Brevet Lieutenant Colonel John Trout Greble (USMA 1854), the first Academy graduate killed in the Civil War (and by some accounts the first Union Regular Army officer killed). 1st Lieutenant Greble fell in combat at the Battle of Big Bethel on June 10, 1861 and was breveted to Captain, Major, and Lt. Colonel before his death.

Edwin St. J. Greble. Source: University of Texas Special Collections.

But back to the story. J. T. Greble had a son, Edwin, born in 1859 who graduated from West Point in 1881. In 1902, after service in the Pacific and in Cuba, he was stationed at West Point as a Senior Instructor in Artillery. On a July day in 1902, Greble had the entire first class of cadets on a march. As part of the drill was a team of horses pulling a gun carriage. A Cadet Collins rode one of the horses pulling the carriage and four cadets were on the back with the gun. From here, I'll quote from the New York Times:

In passing along a road at the foot of "Cro'nest" Mountain, near the intersection of the one leading to Newburg and below which there is an embankment of 13 feet, the lead horse began acting badly, and Capt. Greble ordered Cadet Collins to alight, and he himself mounted the animal. He had no sooner done so than the horse jumped off the embankment, dragging the other three horses with it. The limber turned over, and the heavy gun being wrenched from it, fell down the bank and upon Capt. Greble. Broth his legs were broken below the knee, and he is said to be injured internally. Cadet Moore also was thrown down the bank and badly injured. cadet Phillips sustained some slight bruises and scratches, but the other two cadets jumped and escaped injury.

Fortunately, all survived and appear to have recovered. Greble went on to serve again in Cuba and during the First World War as a Major General in the National Army but was physically unable to deploy to Europe. Whether he suffered from lingering effects of the accident are unknown.

If you like this site, please use a button below to share with your friends.

Source: "Accident at West Point," New York Times, Jul. 13, 1902.

Go West Young Men! And Laundry Girls too!

In 1904, the Corps of Cadets went a long way from home...

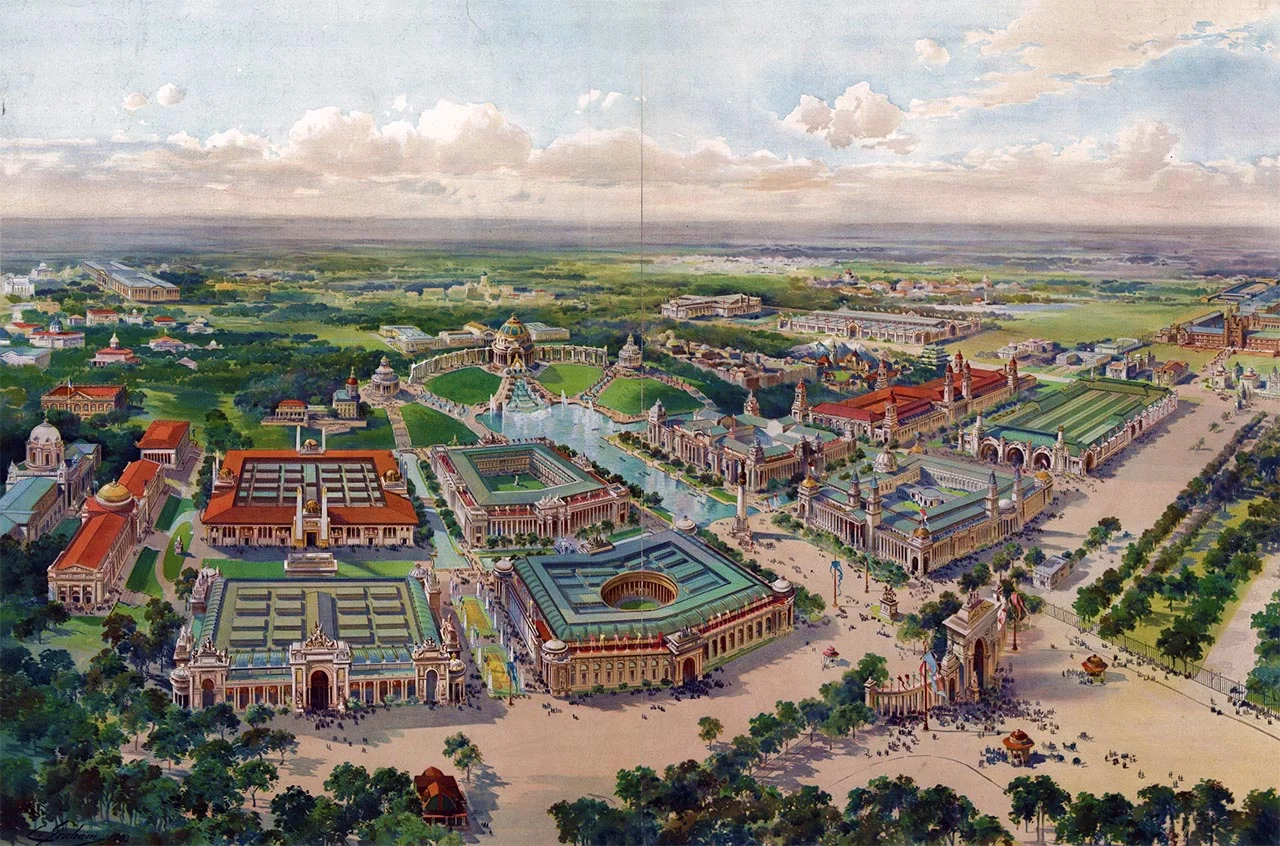

Map of the 1904 World's Fair. Source: World's Fair, St Louis, 1904. Library of Congress.

One of the most significant mass movements in West Point history has to be the trip to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, more commonly known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. In late May of 1904, just after exams but before graduation exercises, nearly the entire Corps headed westward to encamp on the Exposition’s fairgrounds for about 10 days.

This move was a logistical wonder. Four trains were chartered, leaving on two separate days. On the first day (Friday 27 May), the trains consisted of cavalry soldiers, 47 horses, 13 mules, several laundry girls, civilian employees, two mounted guns, and eleven cars full of baggage. The next day, May 28th, the trains carried 407 cadets, the Band, and officers and their wives.

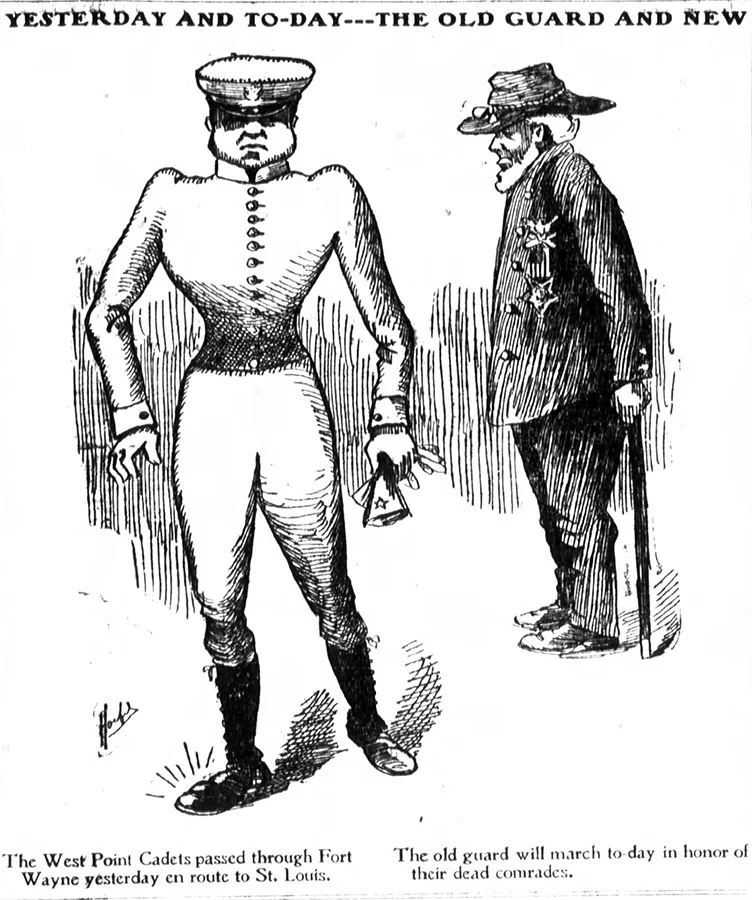

Cartoon of a Cadet and a Civil War veteran sparked by the Corps passing through town on their way to the Exposition. Source: Fort Wayne Gazette, 30 May 1904.

The route taken was complex. First, the trains headed to Buffalo along tracks controlled by the New York Central Railroad. Whether they went north to Albany on the west side of the River or south to Weehawken and then north from Manhattan on the New York Central’s main route is unclear. In Buffalo, the trains transferred to the Lake Shore line of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway. Despite a reported derailment on this leg (which must have been minor), this route brought the Corps as far as Toledo, where the trains transferred again to the Wabash Railroad that allowed fast transport to Decatur and on to St. Louis. Newspapers along the route in towns such as Syracuse, Fort Wayne, and Decatur reported the movement. A planned breakfast stop in Decatur was cancelled when, according to The Daily Review, the train made excellent time and was too early for breakfast.

When the Corps of Cadets arrived in St. Louis on 30 May, they had to set up their encampment, although some work had been done already by enlisted soldiers. The weather was not great and the cadets had to work in mud. The Exposition was open from April to December of 1904 with certain periods of that time having themes. The Cadets were the stars of “Military Week” but shared the spotlight with other military academies and Regular Army troops. Attendance was often over 50,000 people per day. Hundreds of buildings and thousands of sculptures graced the grounds.

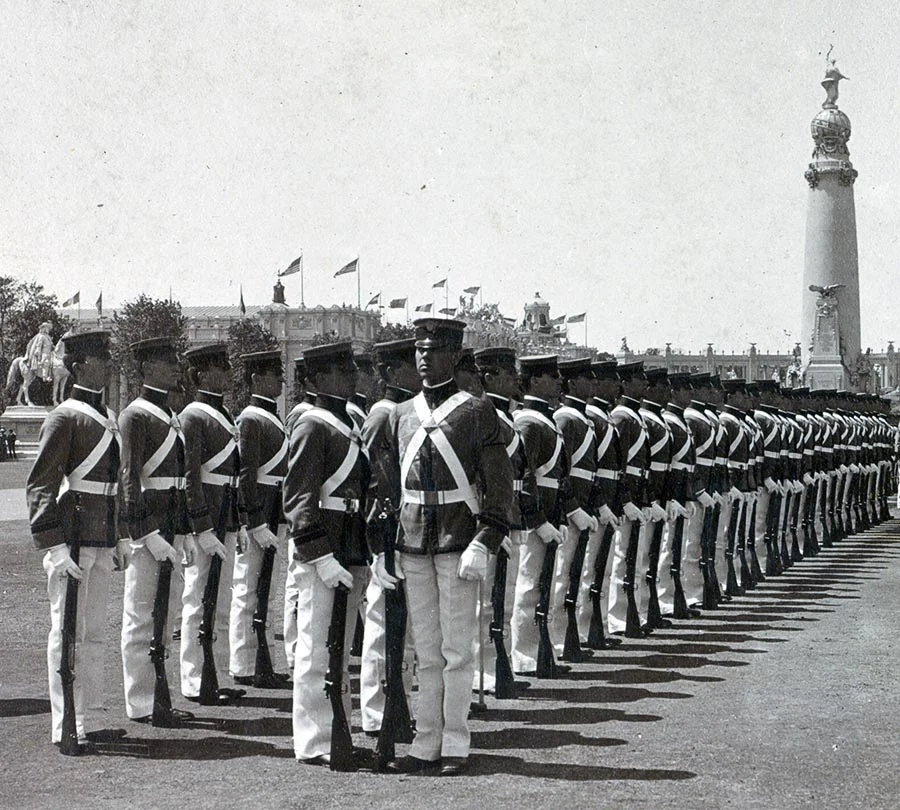

Cadets marching at the Fair. Source: Library of Congress.

On their first day, a large parade was held that included hundreds of Union Civil War veterans. At the end, one paper says that “impromptu” military exercises were held. The cadets spent much of the next week parading, conducting exercises, and basically being shown off.

But, they had time for fun as well. Apparently there were no restrictions on cadet free time and they were allowed to leave the Fair as long as their destinations were approved by an officer. This was apparently necessary to prevent cadets from inviting each other to dinner and then telling their chain-of-command that they had been invited to dine somewhere. Perhaps at the Fair they enjoyed ice cream cones, hot dogs, and Dr. Pepper, all invented earlier but popularized for a national audience at the Exposition.

But not everything went as planned. First, dancing rules had to be issued. For example:

Cadets, dancing with ladies, must dance with their left arm extended and under no circumstances will they be allowed to bend the right elbow so as to draw their partner close to them.

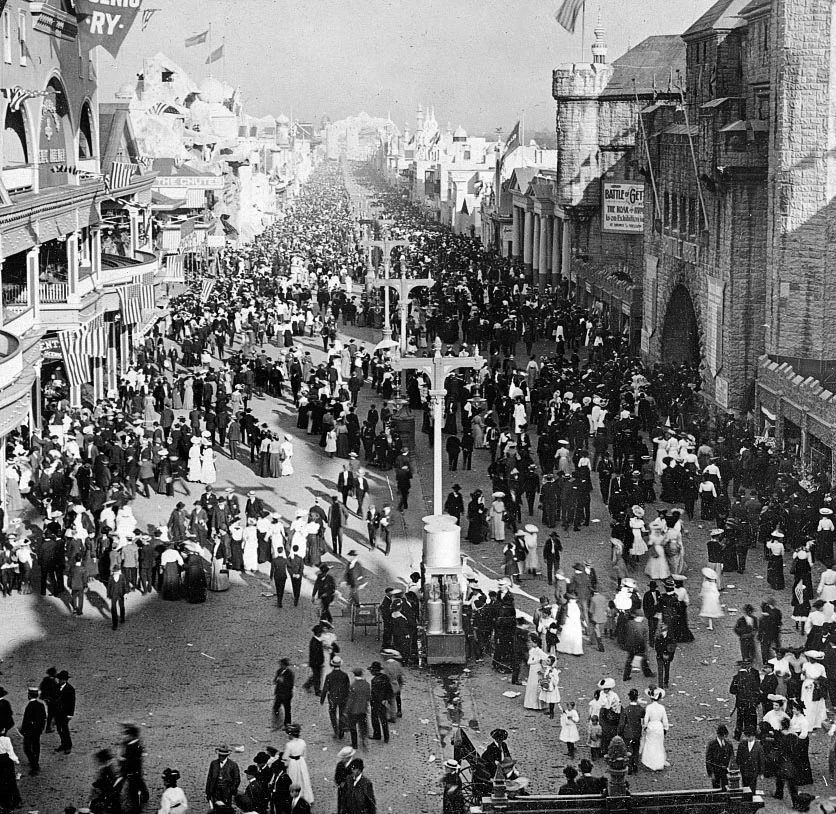

The "Great Pike" at the Exposition. Source: Library of Congress.

Furthermore, social events had to be properly chaperoned. This became a problem when not enough chaperones could be found. The New York Times (9 June 1904) reported on a local newspaper account that said the following:

Inability to find, within the newly drawn circle of One Hundred fifty disengaged matrons to act as chaperons (sic) is the supposed cause of the cancellation by the Board of Lady Managers of the invitations sent out to the reception which was to have been tendered by that important body to the West Point cadets Wednesday evening.

That’s life. Sometimes you get to dance with your left arm extended and sometimes you don’t.

The Cadets returned to West Point in time for mid-June Graduation Exercises.

If you're enjoying this site, please use the buttons at the bottom to share on social media.

Select Sources:

"NO CHAPERONS, NO RECEPTION," New York Times, 9 June 1904.

"Yesterday and To-Day," The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 30 May, 1904.

"West Point Men Charge on Mud," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 May 1904.

"Breakfast Order was Cut Out," The Daily Review (Decatur, IL), 30 May 1904.

"The Board of Visitors — Cadets Starting for St. Louis," Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, 28 May 1904.

General Scott's Fall

General Winfield Scott's 1858 visit to West Point was memorable...

Recently on the Facebook page for this site, I wrote about the very candid news accounts concerning General Winfield Scott's gastrointestinal issues. Today, another look at the hero's health issues. And please remember to share this article to Twitter, FB, etc. by using the buttons at the bottom of the page.

Cozzens' Hotel. Source: NYPL

General Winfield Scott, beloved military hero and failed presidential candidate, spent a great deal of time at West Point as he grew older. In September of 1858, Scott, already over 70 years old and still on active duty, was staying at Cozzens' Hotel in what is now Highland Falls. The large hotel was located close to where now stands a McDonalds. Scott's stay this time would be memorable and garner national press. According to the Louisville Daily Courier:

Gen. Scott had a very severe fall on the stairs at Cozzens' Hotel, West Point, last week... Having had a bullet through one shoulder, and a sword thrust through the other arm during his campaigns, he was unable to break the force of the fall by his arms, and his back was severely injured. He cannot move without great pain. He has been cupped and leeched, and is somewhat better, suffers intensely. At his advanced age, and with so ponderous a frame, it is a serious affair to have such a fall, and he is fortunate to escape with life.

Cupped and leeched! The reference to Scott's ponderous frame refers to the General's weight, which at this point was about 300 pounds. Fortunately, Scott recovered. The Tennessean newspaper reported the following:

General Scott, ~1860. Source: NARA.

General Scott has so far recovered from the effects of his recent fall that he is able to move about and transact his ordinary official and private business. Reports from Cozzens' Hotel, West Point, where hs is stopping, state that he suffered intense pain from the bruises he received, but his constitution is yet so good that he recovered in a surprisingly short time, considering his age and the severity of the accident to a man of his large frame. The old General has evidently stamina enough left to be President one term at least before he dies.

Scott retired to West Point in 1861 amidst the turmoil of politics and military disagreements of the early days of the Civil War. Although a Virginian, he remained loyal to the Union. In total, he served 53 years in the Army. Scott died in 1866 and is buried in the West Point Cemetery. I'm sure we'll explore some of his exploits in the future.

Sources:

"Accident to Gen. Scott," The Louisville Daily Courier, 27 Sep 1858, 1.

"Recovery of Gen. Scott," The Tennessean, 1 Oct 1858, 2.

July 4th, 1817

Look back at the 4th of July at West Point in 1817.

As we celebrate our country's 240th anniversary, let's look back at the 41st birthday celebration held at West Point in 1817 according to a letter to the editor in New York's Evening Post. This article is a bit long and there are no fireworks, but I think it gives insight into what the Academy faculty and cadets valued at the time.

Governor Thomas Worthington by Charles Willson Peale, 1815. Source:Wikipedia.

The main activities kicked off at 3:30 p.m. with a dinner procession consisting of the 2nd company of cadets, the 1st company of cadets, the academic staff, military officers, and invited guests, which included Governor Thomas Worthington of Ohio. The parade processed with musical accompaniment to an arbor created for the celebration. An arbor is a wooden framework covered by plants, tree branches, vines, etc.. There, the cadet companies formed lines and allowed the faculty, officers, and guests to pass.

At 4 p.m., a dinner organized by a cadet committee and prepared by the Steward was served. This would have been in the 1815 mess hall on the Plain near the entrance to the present Washington Hall. After the meal, a long series of toasts with cheers and music were presented. The toasts, in order, were for the following:

1. The 4th of July, accompanied by "Hail Columbia," which was the de facto national anthem of the Country in the 19th century. One gun fired. Six cheers.

2. The President and Vice-President of the United States, with "The President's March." (The exact song is unclear because "Hail Columbia" was also known as "The President's March." This could refer to "Hail to the Chief" which was starting to be used in conjunction with Presidents at about this time.) One gun fired.

3. The Governor and citizens of New York, with an unnamed waltz. Three cheers.

4. The memory of George Washington, the toast made while standing, with "Pleyel's Hymn" ("Children of the Heavenly King"). This was followed by two minutes of gun salutes.

President James Monroe by C.B. King, Engraving by Goodman & Piggot. Source: Library of Congress.

5. The President's Tour. In June of 1817, President James Monroe set off on the first Presidential Tour since George Washington. It lasted 15 weeks and was a great success. This toast was accompanied by "Monroe's March" and three cheers. The song is possible this one.

6. The United States, with a one gun salute, six cheers, and "Yankee Doodle."

7. Poetry and Eloquence. "Republics should always cherish them — national pride, and honor and virtue, result from their perfection." This was followed by three cheers and the "Overture to Artaxerxes" from the Persia-set opera by the English composer Thomas Arne. He also wrote, "A-Hunting We Will Go!"

8. Science. "Let it be cultivated; it purges the mental eye of its film — it burnishes the soul with the rays of divinity." This was accompanied by the "Cadet's grand march" and 3 cheers.

9. Vincent M. Lowe, who had been killed on New Year's Day, 1817. (See my earlier article on Lowe). This toast was drank standing and the musicians played the traditional Irish song "Wounded Hussar."

10. Our Artisans and Mechanics, along with a quick step and three cheers.

11. The Profession of Arms, with a one-gun salute, the "Fort Erie March" and three cheers.

12. Citizens and Soldiers. "Mutual jealousy produces mutual destruction — let them beware of it." The music for this toast was "The Soldier's Return," which probably refers to the Robert Burns song from the 1790's. Lyrics here. Song here.

13. Ireland. "The vampires of freedom which crawl around her vitals suppress not the fire of her genius — national misery and suffering elicit the mental superiority of her sons." This toast included a one-gun salute, six cheers, and the playing of "Erin Go Braugh." Irish immigration and nationalism were on the rise at the time.

14. The French Exiles, with a one-gun salute, six cheers, and the playing of "Downfall of Paris." This toast seems to refer to the three-year occupation of Paris after the Treaty of Paris in 1815. "Downfall of Paris" was a popular fife and drum tune of the day. See the video inset.

15. David Ramsey, a well-known doctor, politician, and historian of the American Revolution, who was murdered in 1815 in Charleston, SC by a man who a judge ordered Ramsey to examine. This toast was drank standing and was accompanied by "The Portuguese Hymn" (a.k.a. "Oh Come All Ye Faithful")

16. Courage, with a trumpet march, three cheers, and a one-gun salute.

17. Man, with the "Overture to St. Jean" and three cheers.

18. Subordination, with a one-gun salute, "Capt. Patridge's quick step," and six cheers. Partridge was the Supe at the time but would be dismissed in November of 1817. That's a story for another day.

19. The Fair. In other words, women. "Like the sparkling wine they seem sweeter as they approach our lips." This toast had six cheers and the band played "Nightingale."

At this point, official toasts ended but volunteers continued on, honoring:

Governor Worthington (presumably Governor Thomas Worthington of Ohio, whose son, Thomas Jr., would graduate in 1827.): The Corps of Engineers and Cadets of the Military Academy.

Captain Alden Partridge: The heroes of the Revolution.

Major Isaac Roberdeau, Topographical Engineer: General Enoch Poor and the New Hampshire Brigade.

Mr. Claudius Berard, Professor of French: The pupils of the Military Academy.

Lieutenant Wright: Fallen brethren.

Lieutenant Blaney: General Arthur St. Clair (a controversial figure from the Revolution).

Cadet Benjamin C. Vining (USMA 1818): Alexander Hamilton.

Cadet S. Stanhope Smith (1818): National Virtue.

Cadet Samuel Ringgold (1818): The President in his tour.

Cadet John C. Kirk (1817): "Our late struggle for national right and national honor."

Cadet Edwin Little (admitted 1814): The Committee of Arrangement.

Cadet William H. James (admitted 1816): General Thomas Sumpter

Cadet John C. Russell (1818), who later became John B. F. Russell: Our Preceptors.

Cadet Benjamin C. Vining (1818): Fisher Ames. Ames was a Federalist politician who died in 1808.

At this point, Governor Worthington and Captain Partridge left, but two more toasts followed:

Cadet Nathaniel H. Loring (dismissed in 1819 under complicated circumstances related to their complaints about harsh treatment by Captain Bliss): Governor Worthington.

Cadet William G. McNeill (1817): Captain Partridge. (McNeill's sister would marry his friend George Washington Whistler and give birth to the famed painter, and West Point dropout, James McNeill Whistler).

After all these toasts, a ball was held. What a long night of celebrating!

Source: The Evening Post (New York), July 12, 1817.

Movable Monuments Part 1: Wood's Monument

A brief history of West Point's Wood's Monument and it's changing location.

This is the first of an occasional series on the moving of West Point monuments. Today, Wood's Monument, one of the Academy's earliest memorials, is the focus.

Eleazar Derby Wood was born in Massachusetts in 1783, entered West Point in May of 1805, and graduated in October of 1806. He then aided in the construction of fortifications in New York Harbor on Governor's Island and what is now Liberty Island (Bedloe's Island at the time). The star-shaped fort on Liberty Island became known as Fort Wood in his honor and is now the base of the Statue of Liberty. He also worked for several years on fortifications in Virginia. During the War of 1812, Wood was sent to the frontier to build forts along Lake Erie under the command of future President William Henry Harrison. Wood successfully held Fort Erie in August of 1814 but was killed in action on September 17 of the same year while leading a sortie to capture nearby British batteries.

Major General Jacob Brown, a hero of the War of 1812, admired Wood and a few years after the war ordered a monument constructed in the fallen grad's honor at West Point, paying for its construction with his own money. Wood's Monument was erected in October of 1818 and was located in the middle of the Plain in front of the 1815 Academy building, which was located about where Eisenhower Barracks now stand. Just a month after its completion, Sylvanus Thayer asked that a railing be put around the obelisk. An 1820 engraving shows the memorial on the Plain.

This 1820 engraving shows the Wood Monument on the Plain in front of the 1815 Academy building. Source: The Analectic Magazine, Vol. 2. 1820, 171.

Wood's Monument stayed in front of the Academy on the Plain for about three years before being moved (in 1821 according to Academy sources) to a small hill that stood just west of the site of the current Firstie Club. This hill, known as Bunker's Hill on early maps, would eventually be called Monument Hill because of Wood's Monument. The obelisk stood on top of the small hill, surrounded by a fence and evergreen trees.

Wood Monument on Monument Hill, possibly from the late 1860s, From the New York Public Library.

By the late 19th century, a plan developed to level the small hill that the Monument stood on and to use the earth to fill in Execution Hollow. This meant that the Monument had to be moved. While some sources say this happened in the 1870s, the monument is clearly visible on an 1883 map of the Academy. Contemporary accounts generally say 1885 and this seems correct because an 1891 shows that the Monument had been moved and the hill it stood upon leveled.

Today, you can see Wood's Monument in the West Point Cemetery even though Wood is not buried there.

If you want to share this article, there are gray social media buttons at the bottom of the page! Thanks!

Wood's Monument, 2016. Photo by Author.

Wood's Monument Location, 1818-Present. Map by Author. Base Map: Google Earth.

Crop of an 1883 map of West Point showing Wood's Monument on a hill near the Ordnance Compound (now known as the Firstie Club).

Crazy First Days as a Cadet, 1814

In his first days as a West Point cadet, George D. Ramsay saw horrific things...

One of the craziest first days as a cadet has to be the experience of future Chief of Ordnance George D. Ramsay, USMA Class of 1820. Ramsay was appointed at just age 12! Setting off from Virginia in August of 1814, the young man and a chaperone made their way by stage to New York City, a journey of about four days passing through Baltimore, Lancaster, and Philadelphia. They arrived at the American Hotel on Broadway to rest before finding passage to West Point. But, because Ramsay was wearing his cadet uniform for the journey, he was recognized and informed that the Corps was actually in the City encamped on Governor's Island. After meeting a couple of cadets, he was invited to join them at the encampment and finish the journey to West Point with the Corps.

Castle Williams on Governors Island, designed and built (1807-1811) by West Point's first Superintendent, Jonathan Williams.

Arriving on Governor's Island, Ramsay settled into one of the cadet tents and unofficially joined the Corps' activities. Because the War of 1812 was still underway, the camp gave a real Army experience for the Corps. This was never clearer than on Ramsay's first full day in camp. The 12-year old was welcomed to the Army by witnessing the execution of a deserter. This poor soul was likely Thomas Fitzgerald, who's death on August 20, 1814 was recorded in The Long-Island Star on August 24th. They reported that Fitzgerald was "shot on Governor's Island pursuant to the sentence of a Court martial, for frequent acts of desertion." What a first day!

George D. Ramsay by Matthew Brady. Source: NARA

Ramsay's experience as a new cadet only got worse. After a sloop trip back to West Point with the Corps, the cadets all headed for the two messes, Mrs. Thompson's (near the current Firstie Club) and one operated by Isaac Partridge on the Plain near the present location of the Supe's House. Ramsay went to Mrs. Thompson's first, but was turned away. He then tried Partridge's and was also barred from entry. Homesick and forlorn, he wandered alone around the Plain until his spirits lifted. Wandering back to Mrs. Thompson's, he was shown kindness by Souverine, Mrs. Thomspon's assistant. Souverine was of African-Caribbean ancestry and was known for her wit and good-humor. With a good meal in him, Ramsay's spirits were lifted and his cadet career was off to a proper start.

Best of luck to the West Point Class of 2020!!

Sources:

Ramsay, George D. "Recollections of Cadet Life of George D. Ramsay," in George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., Third Edition Revised and Extended, Vol. III. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1891.

West Point, from above Washington Valley, 1834

A breakdown of a beautiful 1834 engraving of West Point.

From time to time I'll be annotating old art to help you better understand the past landscapes of the Hudson Valley. Today's installment is West Point, from above Washington Valley, looking down the river, a painted engraving by George Cooke (painter) and W.J. Bennett (engraver). It was published by the New York firm of Parker & Clover circa 1834. Bennett was well-known for his aquatints, a type of engraving that produces a watercolor look. Cooke likely would have painted the original scene and then Bennett would make an engraving that could be printed in quantity. The prints were then hand-colored. Bennett was a member of the National Academy of Design, founded in 1825 by artists including Hudson River School giants Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand as well as Samuel F.B. Morse (-- --- .-. ... .) . Longtime Professor of Drawing at the Academy Robert W. Weir was also a member (after 1829).

First, look at the print (and an enlargement) and then below you'll find a copy with callouts labeling the key features.

Crop of West Point, from above Washington Valley, looking down the river, ~1834 Source: Library of Congress.

Can you identify any of the buildings? Four still exist today (not including monuments and forts). Here's an enlargement:

Enlargement Crop of West Point, from above Washington Valley, looking down the river, ~1834

Ok, here are the annotated copies!

Annotated Art #1

Annotated Art #2

Notes:

- The hill that the people are looking from really doesn't exist anymore. It was modified and eventually level to make way for railroad tracks. It was approximately on the site of the current rugby complex at West Point.

- The South barracks were completed in 1815 along with the Academy building, and the North Barracks were completed in 1817. All three buildings were stone.

- Both the current Superintendent's and Commandant's houses are visible in this artwork, along with other houses built at the time (1819-1820) that no longer exist.

- The three brick houses on Professors' Row (only two are visible here) were all completed in the 1820s. Notice that they do not have the "wings" and porches they have now.

- Wood's Monument stood on a small hill known as Monument Hill (sometimes Bunker's Hill on older maps). The hill no longer exists, having been leveled to create the road that now goes from the Plain to the Firstie Club.

- The West Point Hotel was completed in 1829.

- The Kosciuszko Monument was dedicated in 1828.

- Notice how visible the Cadet Monument is from the River. The trio of visible monuments along with the flagpole were useful navigation ads for sloop and steamboat captains.

- Washington Valley was the site of the Red House owned during the Revolution by the Moore family. The Valley extends inland past what is now the West Point Golf Course.

You can get a free high-resolution copy of the print at the Library of Congress website here.

Thayer Statue Unveiled, 1883

Statue of Sylvanus Thayer in 1902 in its original location near the current entrance to the Mess Hall. Source: American Monthly Review of Reviews, July 1902.

The statue of Colonel Sylvanus Thayer at West Point is one of the Academy’s most recognized monuments. It’s simple inscription, “Colonel Thayer, Father of the Military Academy,” is a testament to his consistent, firm leadership as Superintendent from 1817-1833. In honor of Father’s Day, here are eight facts about the unveiling of the Thayer Monument in June of 1883.

1. Thayer died in 1872 and in the years that followed there was a movement among early graduates to erect a monument to him. Much of the funding came from George Washington Cullum, a member of the Class of 1833, Thayer’s last year as Superintendent. Cullum was also Superintendent from 1864-1866 and is of course known for his Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy (“Cullum Numbers”) and Cullum Hall. The former Superintendent was the primary speaker at the unveiling.

2. The white granite statue was sculpted by German-born Civil War veteran Carl Conrads. A prolific sculptor, he is also known for statues of Alexander Hamilton (in Central Park), and the American Volunteer at the Antietam National Cemetery in Maryland. Conrads worked for the New England Granite Works in Hartford, Connecticut.

3. The Monument was unveiled on June 11, 1883, the day before graduation. According to the New York Times, the weather was hot and Cullum’s speech long, covering Thayer’s entire career. The NYT says the address, presented in the Chapel, “occupied a good many minutes” and described the entire ceremony as “tremendously strung out.”

4. At the end of proceedings in the Chapel, a procession, led by the Academy band, marched to the statue site, which was in the southwest corner of the Plain approximately on the current site of the front entrance of the Mess Hall (Washington Hall). A 10-gun salute accompanied the unveiling and the statue was covered in flags.

This map shows the Thayer Monument on an 1891 map of the Academy. The building just to the west of the barracks (with Mickey Mouse ears) is a gymnasium not present when the statue was unveiled in 1883.

5. Guests in attendance included ex-President General Ulysses S. Grant, USMA Class of 1843, General William Tecumseh Sherman (USMA 1840), Secretary of War Robert Todd Lincoln, Medal of Honor recipient Henry A. Barnum, Confederate Brigadier General Thomas Dockery, and Chief Justice of the New York Court of Common Pleas, Charles P. Daly.

Ulysses S. Grant, date unknown. Source: Bain News Service via Wikipedia.

6. General Grant arrived unannounced according to the New York Times, taking a night train operated by the then-new West Shore Railroad. Its station was near the site of the current South Dock. Because he was unannounced and it was dark, there was nobody to greet Grant or to bring him up the hill (Grant was 61 at the time). The Times reports:

The emphatic remarks the General made on that occasion are still echoing among the hills. After paralyzing the innocent station agent and the baggagemaster and talking about Macomb’s dam and other engineering feats, the General captured an unfortunate blue-coated solder who was prowling around the station without leave and sent him up the hill after a carriage.

Grant stayed with Charles Larned, Professor of Drawing.

7. Two friends from the Class of 1828, Ivers J. Austin and Thomas F. Drayton, were reunited after not seeing each other since their graduation.

8. A mortar and pyrotechnics demonstration at 8 p.m. was followed by a ball held in the mess hall that attracted guests from all over the region. Over 500 people attended the party thrown by the Class of 1884. Dancing began at 10 p.m.. Food was served in the gymnasium at 11:30 (this likely was first floor of the Second Academy, which was on the site of Pershing Barracks and next to the Mess Hall). A german (a type of dance) began at half-past midnight. It is a complicated dance with a leader (like a caller in square dancing) that involved the exchange of small favors (souvenirs). The favors included satin handkerchief pouches for the women and canes for the men. The ball wrapped at 3 a.m., which must have meant some tired cadets at graduation the next day!

Sources:

"Big Guns at West Point," New York Times, June 12, 1883, 1.

"Gen. Sylvanus Thayer," The Tennessean, June 12, 1883, 1.

"The Graduation Ball," New York Tribune, June 12, 1883, 2.

"Statue of Gen. Thayer Unveiled," The Daily Commonwealth (Kansas), June 12, 1883, 1.

Tillman, Samuel E. . 1897. "West Point and its Centenary." The American Monthly Review of Reviews 26 (150):16.

"Unveiling a Statue," The Times (Philadelphia), June 12, 1883, 1.

Lightning Strikes the Flag Pole, 1895

In honor of Flag Day (and the Army's Birthday) comes this story of resiliency from June 30, 1895:

West Point Flag Pole, 19th century, exact date unknown. Source: The New York Public Library

"At 8:30 o’clock this morning the cadets who attend services in the little Catholic church at the foot of the hill assembled in the barracks area. They marched along Professor’s Row, and turned in the path through Trophy Point, where the large flagpole stands. The pole was over 100 feet high. The squad of cadets had just passed, and were not yet thirty feet from the pole, when a vivid flash of lightning came down from Cro’ Nest.

"The detachment of cadets was stunned, and a few fell to the ground, but in less than a minute all had recovered.

"Pieces of wood from three to fifteen feet long were strewn all around them. The big flagpole had been struck by the bolt, and was splintered into thousands of pieces. To-day hundreds of people are viewing the ruined pole, and nearly half of it has been carried away by relic hunters."

A new pole was promised in “a few days” but it seems that it took three months to begin erecting the replacement (mid-October). Its specifications were listed as:

Bottom Section: 97' long made of white pine, 2.5’ in diameter set into a brick-lined hole 14’ feet and filled with concrete.

Top Section: 60’

Total height: 130’

Cost: $1,000

Happy Flag Day!

Sources:

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "View of West Point." New York Public Library Digital Collections.

"A New Flagstaff on Trophy Point," New York Times, October 19, 1895, 10.

"The West Point Flagpole Gone," New York Times, July 1, 1895, 1.

A Problematic Purchase of Polo Ponies

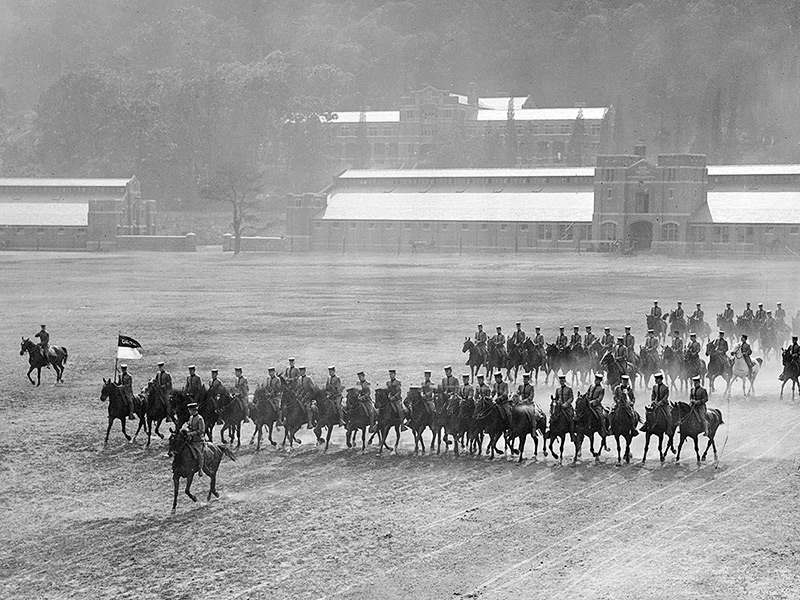

Cavalry Drills at West Point, ~1910-1915. Source: Bain News Service via the Library of Congress.

Polo was in fashion at West Point (and the Army) in the first decade of the 20th century. The game was being played at West Point, often with cavalry horses, at least as early as 1902-03. In 1910, a group of cadets asked the Quartermaster, Lieutenant Colonel John M. Carson, Jr., for eight well-trained horses. Carson thought this was a good idea and polled the cavalry officers assigned to the Academy. They also agreed that the ponies were a good idea and Carson went forward with a $2,000 purchase for the horses. He then sent a bill to Washington for reimbursement.

As you might have guessed, the expense was refused as the horses were not “cavalry, artillery, or engineer horses” and Carson was told he was personally responsible for the purchase. This made him the focus of much ribbing at the Academy. According to the New York Times (1910), Colonel Hugh L. Scott, Superintendent, said to Carson, “I see you own some very fine ponies.” Carson replied, “Indeed I do; at least I suppose I do, but $2,000 is a lot of money for one army officer to have to scrape up.”

What happened to the ponies in unclear, but COL Scott was confident that Carson would not, in the end, have to personally pay for the ponies. He told the Times, “He’s got eight as fine polo ponies as there is in this country. Polo ponies are needed at West Point as the game is of great value in teaching the cadets horsemanship and I am sure that in the end Carson will not have to pay the money.”

Polo ponies became a real issue in the Army budget because of the cost to maintain and move them to competitions. To read a lengthy, and sometimes funny, discussion in Congress about the purchase of polo ponies for West Point, check out the Congressional Record from 1913 here.

BONUS: One of the funniest moments in TV history:

Source: “Polo Ponies Bring Col. Carson Dismay.” New York Times, July 17, 1910.

Getting to West Point, 1818

R-Day is a West Point tradition, but it doesn’t go back to the Academy’s beginnings. In the early 19th century, it was impractical to expect Cadets to arrive on a given day because transportation was so unreliable. For example, a sloop trip from New York to West Point could be less than a day or several days depending on winds and tides. So, new cadets were generally told to report in a certain month or date range. The complexity of getting to the Academy is clear in the memoirs of early cadets. Today, we’ll trace the journey of John Hazelhurst Boneval Latrobe, a member of the Class of 1822 who never graduated because of the untimely death of his father, the famous architect and engineer Benjamin Henry Latrobe, from yellow fever in 1820.

J.H.B. Latrobe by Matthew Brady, c.1860-1865. NARA

J.H.B. Latrobe was appointed in December 1817 when he was just fourteen and was told to report in September of 1818. Latrobe lived in Baltimore. What follows is the path he had to take just to get to the Academy.

Day 1: Latrobe departed Baltimore about 8 or 9 a.m. on a steamboat. The first steamboat operating on the Chesapeake was chartered in 1813, so it was still a new and relatively slow technology. Late in the day, Latrobe reached Frenchtown on the Elk River (just south of the current town of Elkton). The distance traveled was probably about 50-60 miles. Today, Frenchtown doesn’t exist except in road names, but it was a major transportation hub in the early 19th century because people and goods could be off-loaded and then transported overland about 16 miles to New Castle on the Delaware River. This negated the need to take a boat all the way around the Delmarva Peninsula. The road between Frenchtown and New Castle was a toll road operated by the New Castle and Frenchtown Turnpike Company. It’s still quite easy today to follow the same route by traveling along Frenchtown Road east from the site of Frenchtown and then driving Rte. 40 and Rte. 273 into New Castle, Delaware. Latrobe spent his first night in New Castle.

Day 2: From New Castle, Latrobe took a steamboat all the way to Trenton, New Jersey, a distance of about 58 miles. From Trenton, a 25-mile stagecoach ride brought the young man to New Brunswick via the busy Trenton and New Brunswick Turnpike, an almost perfectly straight road. Today, Rte. 1 between the two cities follows much of the original roadbed. The Trenton and New Brunswick Turnpike Company had been chartered in 1803 and lasted (struggled) for 99 years. Latrobe slept in New Brunswick.

New Cadet John H.B. Latrobe's Four Day Journey to West Point, 1818. Map by the Author. ©2016 ExecutionHollow.com. Basemap: Google Earth.

Day 3: From New Brunswick, it was back aboard a steamboat for a 40-mile journey by way of the Raritan River and then up the coast to Manhattan. While dining in New York, Latrobe was told that because the four steamboats operating on the Hudson were slow, he should book passage on an Albany-bound sloop and by doing so could reach West Point by morning. Alas, the wind died by the time his sloop reached the Tappan Zee and then was hit with what Latrobe called a “northwester” that nearly capsized the boat (which were often overloaded).

Day 4: The next morning the winds were more favorable and the sloop made its way north. In the afternoon, about a full day after leaving New York, they reached West Point. But there was no triumphant docking for young Latrobe. As was common in those days, the sloop captain loaded a crew member and Latrobe (with baggage) into a small boat that was towed beside the vessel. When they passed the dock, the small boat was quickly maneuvered into the dock while the sloop continued on and Latrobe had to jump to safety before the small boat was yanked away. Latrobe wrote, “I jumped accordingly — my trunk was pitched after me —and away went the sloop to make the next tack near Constitution island.”

1826 Map of West Point by T.B.Brown showing the location of Gee's Point and Gridley's Tavern. Labels by Author.

The landing was at Gee’s Point, the very tip of West Point and now on Flirtation Walk. At a house near the dock, Latrobe hired a man to carry his trunk and escort him to Gridley’s Tavern, a privately operated establishment which was located about where the corners of Bartlett Hall and Taylor Hall meet today. After walking up a steep and “ill-conditioned” road (which is now Flirtation Walk), Latrobe saw the buildings of the Academy, none of which still stand, for the first time. Traveling along the eastern side of the Plain and through the south gate of the property, he arrived at “Grid’s” and was rewarded for his travels by having to sleep in a bed with two other new cadets.

The next morning John H. B. Latrobe reported to the Adjutant and began his cadet career. His journey had taken about 80 hours. Today, the same trip would take about 4 ½.

If you made it this far, please share this post using the buttons at the bottom of the page or in any way you see fit.

Primary Source:

Latrobe, John H. B. Reminiscences of West Point from September, 1818, to March, 1882. East Saginaw, Mich.,: Evening News, Printers, 1887.

Other Sources:

Brugger, R.J., and E.C. Papenfuse. . Maryland: A New Guide to the Old Line State: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

A Map of the Trenton and New-Brunswick Turnpike-road. [180] Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/73691816.

Railroad, Pennsylvania. 1891. Ceremonies Upon the Completion of the Monument Erected by the Pennsylvania Railroad Co. at Bordentown, New Jersey: To Mark the First Piece of Track Laid Between New York and Philadelphia, 1831, November 12, 1891: Pennsylvania railroad Company

Scharf, J. Thomas. History of Delaware, 1609-1888, Volume 1. Philadelphia: L.J. Richards $ Co., 1888.

West Point: Summer Resort

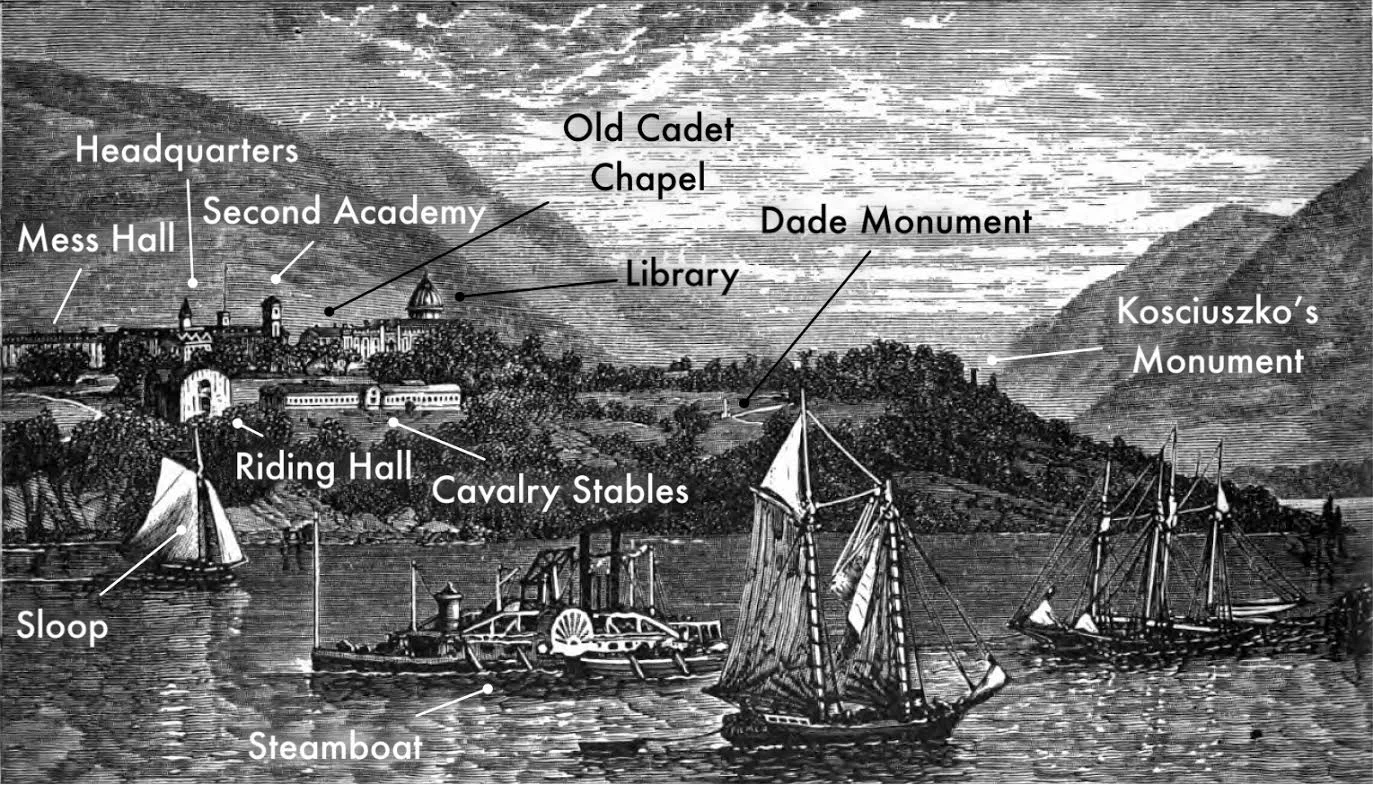

Etching from Appleton's Hand Book of Summer Resorts, 1893

In the 19th century, West Point was a popular summer destination for both American and foreign travelers. At the start of the century, sloops dominated transportation in the Hudson Valley, but predicting arrival time by these large sailboats was nearly impossible. A journey from New York to Albany could take from 1-2 days to 1-2 weeks depending on wind conditions.

Robert Fulton's Steamboat made its maiden voyage in August of 1817, chugging from New York to Albany and back in about four days. In the next three decades, steamboats got faster and dominated traffic until the railroads debuted in the 1840s and 1850s. But, steamboat companies responded to the iron horses by making their vessels more luxurious and boat continued to be the favored mode of travel for Hudson River tourists for the remainder of the century. A stop at West Point along the way was almost a requirement.

The etching above is from the 1893 edition of Appleton's Hand Book of Summer Resorts, which features 2-3 pages on visiting West Point. It recommends visiting in June, July, or August because of the added excitement of cadet summer training on the Plain. Recommended places to visit included Kosciusko's Garden, the Museum of Ordnance and Trophies, the Riding Hall ("open from 11-1 except in summer"), and Trophy Point. Scroll to the bottom to see an annotated copy of the above etching with the buildings labeled.

Because the West Point hotel was on Trophy Point, there was always excitement nearby. Guests could scramble up the hill to Fort Putnam in the morning, relax in Kosciusko's Garden in the afternoon, watch a Cadet parade in the evening, and then socialize at night. How much did a night at the West Point Hotel set you back in 1893? $3.50!

In a future post, we'll talk about dining at West Point. For now, here's your guide to the image above:

Labeled copy of graphic from the 1893 edition of Appleton's Hand Book of Summer Resorts.

Source: Appleton's Hand Book of Summer Resorts. New York: D. Appleton & Co. 1893.

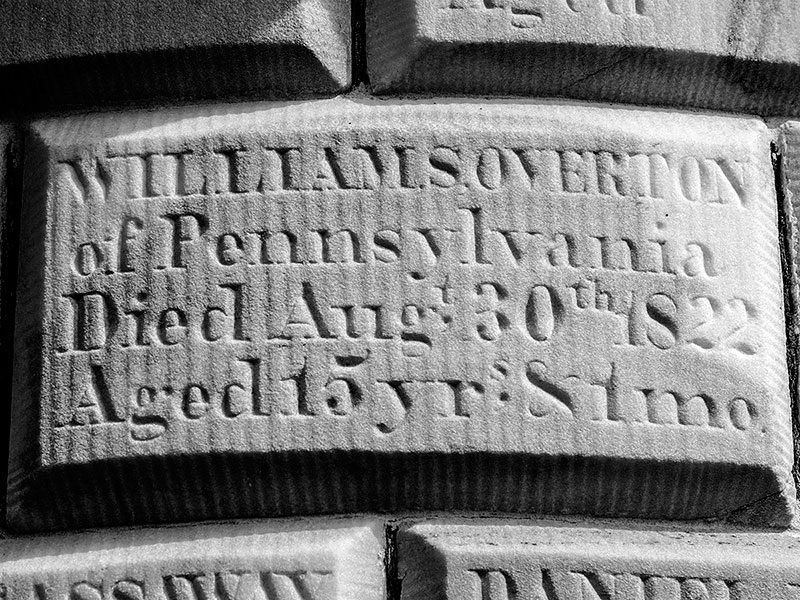

Cadet Monument: William S. Overton

The third in a series of posts on the Cadet Monument, focusing this time on Cadet William S. Overton.

This is the third in a series of posts on the Cadet Monument in honor of Memorial Day.

Cadet Monument marker for Cadet William S. Overton. Photo ©2016

Although dedicated to Vincent M. Lowe, the names of other deceased cadets (as well as officers) were added to the Cadet Monument for decades. One of them is Cadet William S. Overton. Below is a death notice that appeared in the Nashville Whig in October of 1822.

Nashville Whig, 10/2/1822

Departed this life; at the Military Academy, West Point, on the 31st August last, Cadet William S. Overton, son of Gen. Thomas Overton of this vicinity. He died of the Typhus Fever, after a lingering and painful illness of four weeks. His remains were interred with military honors, attended by the members of the institution, who deeply lamented his untimely loss. In the death of this young man, his friends and relations have ample cause to mourn in anguish and sorrow. He has left a kind and affectionate father and mother, with brothers and a sister, to weep over his early and premature departure. At the early age of fourteen, he possessed many attributes of character, which gave every assurance, that he would be a man of usefulness and an ornament to society. But he has been cut off in the dawn of life, when all hopes and expectations of his parents and friends, were blasted forever.

“Ah! dear hapless boy, art thou gone?

“Great support of our languishing years,

“Hast thou left thy fond parents alone,

“To wear out life’s evening in tears.”

Trivia: William's father, General Thomas Overton, served as Andrew Jackson's second, or assistant, in the future President's 1806 duel with Charles Dickinson. The elder Overton administered the duel in which Jackson was injured and Dickinson was killed. Jackson was shot first in the chest but by the rules was allowed to return fire while Dickinson stood still. Old Hickory's pistol didn't fire, so he re-cocked and delivered a wound to Dickinson that killed him later that night.