Where Did Cadets Live, Pt 1

This is a summary of a series that first appeared on my Instagram account.

A fan of the site asked about where cadets lived over the years. Over a series of posts, we’ll explore the first century of cadet living. From 1801 until 1815, the main cadet housing was the wooden Long Barracks, aka the Yellow Barracks, on Trophy Point near the current Battle Monument. It was definitely painted a yellow ochre color at times. It predated the Academy & may have been built during the Revolution, but that’s a topic for another day.

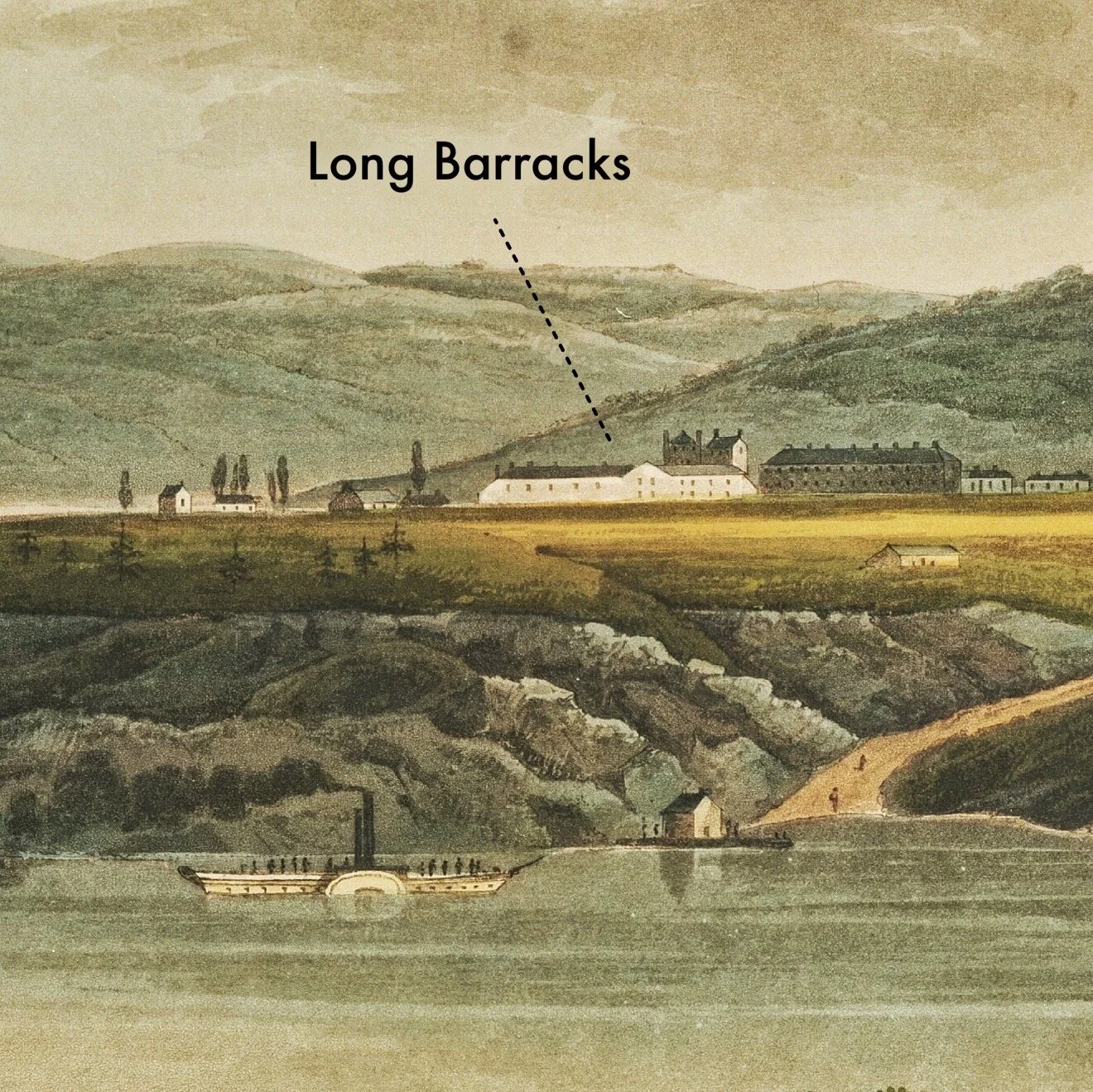

The Long Barracks, as shown in an 1820s engraving by Milbert. Source: New York Public Library

The location of the Long Barracks in relation to current buildings. Base Map: Google Earth.

The Long Barracks was two stories with external stairs & stoops. On the western end was an addition used as a jail. The barracks had large basic rooms with open fireplaces. Cadets had to saw their own wood & retrieve water down the hill over the edge of the Plain in the vicinity of the band shell. Cadets occupied the upper floor & soldiers the lower. In 1815 cadets moved to new barracks & the Long Barracks were thereafter often called the Bombardier Barracks because artillery soldiers occupied it. Some families lived in it as well.

The Long Barracks based on an 1818 map. Source” Author

The Long Barracks burned early on the morning of 20 February 1826. Some histories get the date really wrong and say that the fire was in December or in 1825 or 1827, but the day is supported by multiple sources. For example, on the day of the blaze, the post Quartermaster Aeneas Mackay sent a letter to Quartermaster General Thomas Jessup:

I have the honor to report to you that about 5 O’Clock this morning the Barracks occupied by Company A of the 2° Reg of Artillery stationed at this post and the Military Academy Band, took fire and in the course of two hours was burnt to the ground.- February 20, 1826

There are also cadet accounts of the fire. The conflagration may have started in the guard room when a soldier fell asleep. The old wooden building was engulfed before a bucket brigade could even be formed. Cadets rushed to the scene & helped save the soldiers & families living there. No lives were reported lost! Cadet Albert Church recalled the following in his memoirs, and this is my favorite West Point quote of all time:

I think before a single pail of water was thrown upon it, the whole building was in flames, and with nearly all its contents, save the men, their families, and the largest and most confused collection of large rats that I ever saw, was consumed, even the guns of the soldiers in the guard-rooms.

A view of the Long Barracks in the 1822-1825 time frame. Artist: John Hill. Source: NYPL

Next in the series will be the old South Barracks!

Selected Sources:

Church, Albert E. Personal reminiscences of the Military Academy from 1824 to 1831 : a paper read to the U.S. Military Service Institute, West Point, March 28, 1878. United States Military Academy Library Special Collections.

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. "West Point at the Moment of Exercise" New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The Untimely Death of Cadet James G. Carter

The sad, accidental death of West Point Cadet James G. Carter.

The Cadet Monument, West Point, NY

Photo by Author

In the West Point Cemetery is the Cadet Monument, dedicated in 1818 to honor Cadet Vincent Lowe, killed on New Year’s Day, 1817. On the column of the monument are the names of other cadets who perished while at the Academy. One of these names is James G. Carter. His marker reads, “JAMES G. CARTER of Virginia. Died June 2nd 1835. Aged 18 yrs & 2 mos.” The story of his death is a sad and remarkable one.

On Monday June 1, 1835, Cadet Theodore M.V. Kennedy from Virginia, only 16 years old, was fencing with Cadet Carter in their room (likely North Barracks) without masks and without buttons on the end of the foils (or by one account the button fell off). Kennedy struck at his friend and the point hit below Carter’s eye. Kennedy ran screaming for help from the room and other cadets responded. Carter was found collapsed on the floor with a trickle of blood flowing from the wound. Although the injury looked minor, the foil had entered the brain. The surgeon was sent for and cadets put Carter on his bed and tended to him. He briefly regained consciousness but quickly fell into a delirious state what sounds like a coma. He died the next morning about nine hours after the accident. Kennedy was naturally quite shaken by the accident.

Cadet Kennedy never graduated. He became an artist and in 1838 traveled to Europe to study on the USS Brandywine. How did an artist get passage on a Navy ship? Perhaps it was not uncommon, but Kennedy’s father was naval officer Commodore Edmund Pendleton Kennedy (1785-1844), a veteran of the First Barbary War and the War of 1812. Kennedy was the first commander of the East India Squadron, set up in the 1830s to protect U.S. (economic) interests in East Asia.

Kennedy died suddenly in February of 1849 at Oden’s Hotel in Martisburg, Virginia (now West Virigina). He had been working on a painting the day before and had attended a party with friends that night. One of Kennedy’s friends was artist and future Union brevet Brigadier General David Hunter Strother, known nationally for his personal account of the Civil War and his humorous writings under the pseudonym “Porte Crayon.”

Cadet Carter also had famous relatives. One of his uncles was James Gibbons, called the “Hero of Stony Point” for his gallantry during the 1779 battle not far from West Point. Gibbons became a customs collector in Richmond and corresponded regularly with Thomas Jefferson.

Selected Sources:

Charleston Daily Courier. 6 February, 1849.

Evening Post (New York). 5 June 1835.

Melancholy Occurrence. Vermont Gazette,. 9 June 1835.

Naval. New York Daily Herald. 8 October 1839.

West Point, June 2. Charleston Daily Courier, 18 June 1835.

Movable Monuments Part 1: Wood's Monument

A brief history of West Point's Wood's Monument and it's changing location.

This is the first of an occasional series on the moving of West Point monuments. Today, Wood's Monument, one of the Academy's earliest memorials, is the focus.

Eleazar Derby Wood was born in Massachusetts in 1783, entered West Point in May of 1805, and graduated in October of 1806. He then aided in the construction of fortifications in New York Harbor on Governor's Island and what is now Liberty Island (Bedloe's Island at the time). The star-shaped fort on Liberty Island became known as Fort Wood in his honor and is now the base of the Statue of Liberty. He also worked for several years on fortifications in Virginia. During the War of 1812, Wood was sent to the frontier to build forts along Lake Erie under the command of future President William Henry Harrison. Wood successfully held Fort Erie in August of 1814 but was killed in action on September 17 of the same year while leading a sortie to capture nearby British batteries.

Major General Jacob Brown, a hero of the War of 1812, admired Wood and a few years after the war ordered a monument constructed in the fallen grad's honor at West Point, paying for its construction with his own money. Wood's Monument was erected in October of 1818 and was located in the middle of the Plain in front of the 1815 Academy building, which was located about where Eisenhower Barracks now stand. Just a month after its completion, Sylvanus Thayer asked that a railing be put around the obelisk. An 1820 engraving shows the memorial on the Plain.

Wood's Monument stayed in front of the Academy on the Plain for about three years before being moved (in 1821 according to Academy sources) to a small hill that stood just west of the site of the current Firstie Club. This hill, known as Bunker's Hill on early maps, would eventually be called Monument Hill because of Wood's Monument. The obelisk stood on top of the small hill, surrounded by a fence and evergreen trees.

By the late 19th century, a plan developed to level the small hill that the Monument stood on and to use the earth to fill in Execution Hollow. This meant that the Monument had to be moved. While some sources say this happened in the 1870s, the monument is clearly visible on an 1883 map of the Academy. Contemporary accounts generally say 1885 and this seems correct because an 1891 shows that the Monument had been moved and the hill it stood upon leveled.

Today, you can see Wood's Monument in the West Point Cemetery even though Wood is not buried there.

If you want to share this article, there are gray social media buttons at the bottom of the page! Thanks!