The Untimely Death of Cadet James G. Carter

The sad, accidental death of West Point Cadet James G. Carter.

The Cadet Monument, West Point, NY

Photo by Author

In the West Point Cemetery is the Cadet Monument, dedicated in 1818 to honor Cadet Vincent Lowe, killed on New Year’s Day, 1817. On the column of the monument are the names of other cadets who perished while at the Academy. One of these names is James G. Carter. His marker reads, “JAMES G. CARTER of Virginia. Died June 2nd 1835. Aged 18 yrs & 2 mos.” The story of his death is a sad and remarkable one.

On Monday June 1, 1835, Cadet Theodore M.V. Kennedy from Virginia, only 16 years old, was fencing with Cadet Carter in their room (likely North Barracks) without masks and without buttons on the end of the foils (or by one account the button fell off). Kennedy struck at his friend and the point hit below Carter’s eye. Kennedy ran screaming for help from the room and other cadets responded. Carter was found collapsed on the floor with a trickle of blood flowing from the wound. Although the injury looked minor, the foil had entered the brain. The surgeon was sent for and cadets put Carter on his bed and tended to him. He briefly regained consciousness but quickly fell into a delirious state what sounds like a coma. He died the next morning about nine hours after the accident. Kennedy was naturally quite shaken by the accident.

Cadet Kennedy never graduated. He became an artist and in 1838 traveled to Europe to study on the USS Brandywine. How did an artist get passage on a Navy ship? Perhaps it was not uncommon, but Kennedy’s father was naval officer Commodore Edmund Pendleton Kennedy (1785-1844), a veteran of the First Barbary War and the War of 1812. Kennedy was the first commander of the East India Squadron, set up in the 1830s to protect U.S. (economic) interests in East Asia.

Kennedy died suddenly in February of 1849 at Oden’s Hotel in Martisburg, Virginia (now West Virigina). He had been working on a painting the day before and had attended a party with friends that night. One of Kennedy’s friends was artist and future Union brevet Brigadier General David Hunter Strother, known nationally for his personal account of the Civil War and his humorous writings under the pseudonym “Porte Crayon.”

Cadet Carter also had famous relatives. One of his uncles was James Gibbons, called the “Hero of Stony Point” for his gallantry during the 1779 battle not far from West Point. Gibbons became a customs collector in Richmond and corresponded regularly with Thomas Jefferson.

Selected Sources:

Charleston Daily Courier. 6 February, 1849.

Evening Post (New York). 5 June 1835.

Melancholy Occurrence. Vermont Gazette,. 9 June 1835.

Naval. New York Daily Herald. 8 October 1839.

West Point, June 2. Charleston Daily Courier, 18 June 1835.

West Point, from above Washington Valley, 1834

A breakdown of a beautiful 1834 engraving of West Point.

From time to time I'll be annotating old art to help you better understand the past landscapes of the Hudson Valley. Today's installment is West Point, from above Washington Valley, looking down the river, a painted engraving by George Cooke (painter) and W.J. Bennett (engraver). It was published by the New York firm of Parker & Clover circa 1834. Bennett was well-known for his aquatints, a type of engraving that produces a watercolor look. Cooke likely would have painted the original scene and then Bennett would make an engraving that could be printed in quantity. The prints were then hand-colored. Bennett was a member of the National Academy of Design, founded in 1825 by artists including Hudson River School giants Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand as well as Samuel F.B. Morse (-- --- .-. ... .) . Longtime Professor of Drawing at the Academy Robert W. Weir was also a member (after 1829).

First, look at the print (and an enlargement) and then below you'll find a copy with callouts labeling the key features.

Can you identify any of the buildings? Four still exist today (not including monuments and forts). Here's an enlargement:

Ok, here are the annotated copies!

Notes:

- The hill that the people are looking from really doesn't exist anymore. It was modified and eventually level to make way for railroad tracks. It was approximately on the site of the current rugby complex at West Point.

- The South barracks were completed in 1815 along with the Academy building, and the North Barracks were completed in 1817. All three buildings were stone.

- Both the current Superintendent's and Commandant's houses are visible in this artwork, along with other houses built at the time (1819-1820) that no longer exist.

- The three brick houses on Professors' Row (only two are visible here) were all completed in the 1820s. Notice that they do not have the "wings" and porches they have now.

- Wood's Monument stood on a small hill known as Monument Hill (sometimes Bunker's Hill on older maps). The hill no longer exists, having been leveled to create the road that now goes from the Plain to the Firstie Club.

- The West Point Hotel was completed in 1829.

- The Kosciuszko Monument was dedicated in 1828.

- Notice how visible the Cadet Monument is from the River. The trio of visible monuments along with the flagpole were useful navigation ads for sloop and steamboat captains.

- Washington Valley was the site of the Red House owned during the Revolution by the Moore family. The Valley extends inland past what is now the West Point Golf Course.

You can get a free high-resolution copy of the print at the Library of Congress website here.

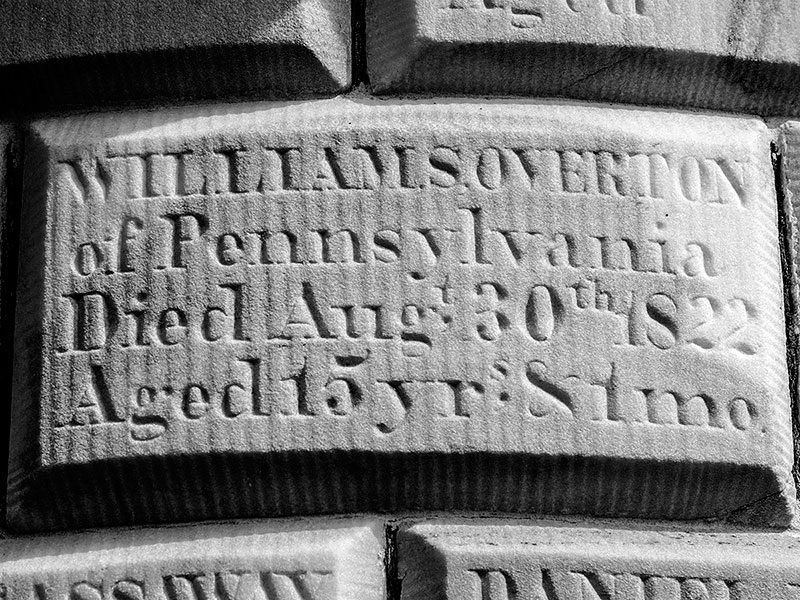

Cadet Monument: William S. Overton

The third in a series of posts on the Cadet Monument, focusing this time on Cadet William S. Overton.

This is the third in a series of posts on the Cadet Monument in honor of Memorial Day.

Although dedicated to Vincent M. Lowe, the names of other deceased cadets (as well as officers) were added to the Cadet Monument for decades. One of them is Cadet William S. Overton. Below is a death notice that appeared in the Nashville Whig in October of 1822.

Nashville Whig, 10/2/1822

Departed this life; at the Military Academy, West Point, on the 31st August last, Cadet William S. Overton, son of Gen. Thomas Overton of this vicinity. He died of the Typhus Fever, after a lingering and painful illness of four weeks. His remains were interred with military honors, attended by the members of the institution, who deeply lamented his untimely loss. In the death of this young man, his friends and relations have ample cause to mourn in anguish and sorrow. He has left a kind and affectionate father and mother, with brothers and a sister, to weep over his early and premature departure. At the early age of fourteen, he possessed many attributes of character, which gave every assurance, that he would be a man of usefulness and an ornament to society. But he has been cut off in the dawn of life, when all hopes and expectations of his parents and friends, were blasted forever.

“Ah! dear hapless boy, art thou gone?

“Great support of our languishing years,

“Hast thou left thy fond parents alone,

“To wear out life’s evening in tears.”

Trivia: William's father, General Thomas Overton, served as Andrew Jackson's second, or assistant, in the future President's 1806 duel with Charles Dickinson. The elder Overton administered the duel in which Jackson was injured and Dickinson was killed. Jackson was shot first in the chest but by the rules was allowed to return fire while Dickinson stood still. Old Hickory's pistol didn't fire, so he re-cocked and delivered a wound to Dickinson that killed him later that night.

Cadets' Monument, 1820

This hand-colored etching of the Cadet Monument (often called the "Cadets' Monument" in early writings) is by English-born artist John Rubens Smith and is thought to be from about 1820 (certainly 1819-1825).

Fun things to notice (see the infographic below):

- One of the women on the left of the Monument is sharing a gaze with the cadet leaning against the tree in the middle. The Monument was a popular attraction for West Point visitors and cadets loved any chance to mingle.

- Notice the cadets taking a shortcut and coming up the bank from the River.

- At the far right, in the background, you can see part of the yellow Long Barracks that burned down in the mid-1820s.

- Also in the background is the old dock, located at about the site of the current helipad. At the time, steamboats were still rare on the river and most boats were sloops.

"The Single Discharge of a Cannon": The Cadet Monument

In honor of Memorial Day, this week’s focus is on the Cadet Monument, one of the Academy’s oldest memorials. It stands in the northeast corner of the West Point Cemetery overlooking the Hudson. Today, I'll detail the sad origins of the Monument. Later this week, I’ll explore its importance later in the 19th century.

On New Year’s Day, 1817, Cadet Vincent M. Lowe enjoyed an early lunch of cider and cakes with his friend Charles Davies, a new Assistant Professor of Mathematics and two years Lowe’s junior. It was an unusually warm winter's day, so the friends sat on the veranda of the military storekeeper’s quarters (later known as the Thompson House and roughly on the site of Mac Short Barracks). Lowe had been born on Navy Island near Niagara Falls where his father, Cornelius Lowe, had been granted land after the Revolution. Cornelius later died at or after the Battle of Queenston Heights during the War of 1812. Davies would go on to be a giant in early American mathematics education, a professor at several colleges, and the author of widely used textbooks.

After their lunch, Lowe had to report to a detail responsible for firing off a 24-gun salute at noon to usher in the New Year. Lowe left Davies near the Academy building (close to where the Superintendent’s house now stands) and set off to his duty location. Not long after, Davies heard a lone cannon discharge, which he deemed unusual, and ran to the cannons where he found his friend dead. Without even a bruise on his body, Lowe had been killed from the percussive force of a round igniting prematurely.

Because of the limited staffing and isolation of the Post in those days, there was no one to prepare the body for burial, so Davies and another man rowed the body all the way to Newburgh without even wearing overcoats, a distance of about seven miles! The Academy’s first graduate, Joseph Gardner Swift (Class of 1802) described the funeral as “one of the most impressive scenes in its march across the plain to the burial ground on the extremity of the German flat, in a gusty snow storm, which alternately concealed and exposed the party in its route.”

Days later, New York’s The Evening Post (January 6, 1817) reported the incident:

Suddenly, at West-Point, on the 1st instant, Cadet VINCENT M. LOWE, aged 18 years. He was killed by the accidental explosion of a charge of powder in a cannon, while ramming the cartridge; the accident is supposed to have occurred in the consequence of an imperfect spunging (sic) of the piece after a previous discharge. Cadet Lowe was an amiable and intelligent youth. His death has deprived the Military Academy of one of its ornaments, and the nation of a promising young soldier.

The Corps of Cadets, moved by Lowe’s death, donated money to erect a monument in his name. Unveiled in 1818, the Cadet Monument reads on one side,

Vincent M. Lowe of New York. This stone feebly testifies the respect and regret of his Brother Cadets. He was accidentally killed by the discharge of a cannon at West Point on 1st. Jan. 1817, aged 19 years.

On the reverse,

This Monument Sacred to the memory of the deceased Officers and Cadets of the Military Academy. Erected by the members of the Institution, Oct. 1818.

It is this reverse message that represents the importance of the Monument over time because for decades it became a tradition to inscribe on the Monument the names of cadets or professors who died while at the Academy.

In a later post, we’ll explore the Cadet Monument beyond Cadet Lowe’s untimely death.

Note: The Monument states that Lowe was 19 years old when he died, but Lowe genealogies record a birth date of January 7, 1796. This would make Lowe 20 years (and almost 21) at the time of his death.

Sources:

Berard, Augusta B. Reminiscences of West Point in the Olden Time: Derived from Various Sources, and Register of Graduates of the United States Military Academy. East Saginaw, MI: Evening News Printing & Binding House, 1886.

"Died." The Evening Post (New York, NY), January 6, 1817.

Swift, Joseph G. The Memoirs of Gen. Joseph Gardner Swift, LL.D., U.S.A., First Graduate of the United States Military Academy, West Point, Chief Engineer U.S.A. from 1812-to 1818. Worcester, MA: F. S. Blanchard & Co., 1890.

"Vincent M. LOWE (7 Jan 1796 - 1 Jan 1817)." Accessed May 29, 2016. https://jrm.phys.ksu.edu/genealogy/needham/d0005/I462.html.