The Untimely Death of Cadet James G. Carter

The sad, accidental death of West Point Cadet James G. Carter.

The Cadet Monument, West Point, NY

Photo by Author

In the West Point Cemetery is the Cadet Monument, dedicated in 1818 to honor Cadet Vincent Lowe, killed on New Year’s Day, 1817. On the column of the monument are the names of other cadets who perished while at the Academy. One of these names is James G. Carter. His marker reads, “JAMES G. CARTER of Virginia. Died June 2nd 1835. Aged 18 yrs & 2 mos.” The story of his death is a sad and remarkable one.

On Monday June 1, 1835, Cadet Theodore M.V. Kennedy from Virginia, only 16 years old, was fencing with Cadet Carter in their room (likely North Barracks) without masks and without buttons on the end of the foils (or by one account the button fell off). Kennedy struck at his friend and the point hit below Carter’s eye. Kennedy ran screaming for help from the room and other cadets responded. Carter was found collapsed on the floor with a trickle of blood flowing from the wound. Although the injury looked minor, the foil had entered the brain. The surgeon was sent for and cadets put Carter on his bed and tended to him. He briefly regained consciousness but quickly fell into a delirious state what sounds like a coma. He died the next morning about nine hours after the accident. Kennedy was naturally quite shaken by the accident.

Cadet Kennedy never graduated. He became an artist and in 1838 traveled to Europe to study on the USS Brandywine. How did an artist get passage on a Navy ship? Perhaps it was not uncommon, but Kennedy’s father was naval officer Commodore Edmund Pendleton Kennedy (1785-1844), a veteran of the First Barbary War and the War of 1812. Kennedy was the first commander of the East India Squadron, set up in the 1830s to protect U.S. (economic) interests in East Asia.

Kennedy died suddenly in February of 1849 at Oden’s Hotel in Martisburg, Virginia (now West Virigina). He had been working on a painting the day before and had attended a party with friends that night. One of Kennedy’s friends was artist and future Union brevet Brigadier General David Hunter Strother, known nationally for his personal account of the Civil War and his humorous writings under the pseudonym “Porte Crayon.”

Cadet Carter also had famous relatives. One of his uncles was James Gibbons, called the “Hero of Stony Point” for his gallantry during the 1779 battle not far from West Point. Gibbons became a customs collector in Richmond and corresponded regularly with Thomas Jefferson.

Selected Sources:

Charleston Daily Courier. 6 February, 1849.

Evening Post (New York). 5 June 1835.

Melancholy Occurrence. Vermont Gazette,. 9 June 1835.

Naval. New York Daily Herald. 8 October 1839.

West Point, June 2. Charleston Daily Courier, 18 June 1835.

The July 4th Riot of 1800

On the Fourth of July in 1800, there was a riot between West Point soldiers and patrons at a local tavern.

On July 4th, 1800, before the Academy even existed as a formal entity, a bloody riot broke out yards from the post at North’s Tavern. A combination bar, restaurant, event hall, and hotel, North’s was located approximately at the corner between Bartlett and Taylor Halls, where the bridge goes over to Thayer Hall. The boundary of the Government’s property was less than 100 feet away! The public house was a source of periodic angst for West Point commanders and by 1798, an order was on the books that no soldier was to go there without written permission. To enforce this rule, patrols from the garrison would periodically check the tavern for violators. According to West Point officials, local patrons would often attempt to start fights with soldiers at North’s.

North's Tavern was located just feet from the southern boundary of West Point property. The establishment became Gridley's in the 1810s and was bought by the Government in 1824 to eliminate the temptation. It was after this that Benny Haven's became famous.

On that fateful holiday, a large group of people from the surrounding mountains had come to North’s to celebrate. Captain James Stille, the garrison commander at West Point, claimed to have seen fighting at the tavern that spread across the Post boundary. When he subsequently sent a patrol to check out the fracas, the soldiers were reportedly disarmed and bloodied by the partygoers. When a soldier reported that people were being murdered. Stille set off to the barracks to round up reinforcements for an orderly response, but on his way he was met by angry troops, muskets in hand with bayonets affixed, storming towards the drinkery.

Thomas North, the proprietor, told a different version of the same incident. He claimed that an armed soldier barged into a dance on the second floor of the inn and refused to leave when asked. When asked a second time, according to North, a fight broke out and the soldier shoved his bayonet at him. North deflected it and the soldier, John Quirk, tumbled down the stairs with a civilian who had grabbed hold of Quirk's musket. At the bottom of the stairs was an outside door where other soldiers were waiting. They soldiers charged forth with their bayonets and those in the tavern defended themselves with chairs. After a scuffle, the soldiers retreated and gathered up their comrades.

As the angry soldiers approached, the local revelers retreated inside and formed a defense line at the top of a stairway. Armed with weapons they had taken from the patrol as well as clubs and stones, a vicious fight commenced in the stairway. The soldiers were “beat back with lots of blood.” Stille appears to have ordered the soldiers to surround the house, but it’s clear a great deal of commotion took place. North claimed that nine windows were smashed as soldiers threw stones into the structure. Several patrons were apparently injured. Some women inside tried to escape the fight by climbing into the attic by way of loose floor boards. North also claimed that the soldiers trashed the bar and stole money and alcohol before forcing the innkeeper’s fourteen-year-old son out of the house at the point of a bayonet. Further, he alleged that the soldier mentioned above, John Quirk threatened to “bash out” his wife’s brains until another soldier came to her rescue.

After some time, Captain Stille was able to end the melee and several people were taken to the guard house for questioning. North claimed that Stille threatened to fire a cannon at the house if the remaining patrons did not surrender. In the end, it is unclear if any charges were filed. Stille wrote to Major General Alexander Hamilton for advice and the future Broadway star recommend turning over any unreleased civilians to local authorities and to be cooperative in any civil matters against soldiers involved.

You can read Stille’s letter to Alexander Hamilton here, and Hamilton’s response here. Thomas North's account can be read in the July 29, 1800, edition of the Poughkeepsie Journal (p.4), available through a subscription to Newspapers.com.

Tales of Ninny

Tales of cadet shenanigans from the 1830s...

Here's an account of a poor lieutenant named Ninny (real name Nathaniel Sayre Harris, USMA Class of 1825) and a few cadets that harassed him so much that he left the Army. Obviously, this would not stand today, but the story gives insight into cadet shenanigans in the early 1800s. The story involves Cadets Arnold Harris and Forbes Britton of the Class of 1834, as well as Cadet Benjamin (Benny) Roberts of the Class of 1835. Ninny was an Assistant Instructor of Infantry Tactics known as a disciplinarian fond of writing cadets up for violations (called "skinning" in the old days). What follows was published in a September 1878 issue of the Army and Navy Journal, complete with 19th-century words and grammar. The language is so fun that I thought it would be best to publish it word-for-word. When you're done, please share and consider joining our growing mailing list.

"Our three worthies hated Ninny with a hatred unspeakable, and they made his life a torment to him. One winter morning, when the reveille roll call was long before day light, Ninny was officer in charge, and he took his stand near the old North Barrack door and near the coal pile to see that everything went on properly. Benny Roberta spied him, and pretending to take him for a post he walked deliberately up to him, and he had commenced to put a serious indignity upon him when Ninny attempted to seize him. Benny had short legs, but he could run like a scared wolf, and he "lit out " with Ninny after him. He took down to the end of South Barracks, then around It and up through the Sally-port and over towards the North Barracks hall door. Ninny was gaining on him, when Benny threw his arm around a post near the coal pile fence and swung himself quickly around. Ninny was close after him, but in turning the post his sword got foul in some way and he fell. Benny was in the barracks in an instant and the chase was given up. Of course all made a great deal of fun, but it was very dark, and it is very doubtful whether any one in the corps knew at the time who it was that Ninny was after.

The barracks mentioned in the story were located on the Plain near the corner of the Library and Eisenhower Barracks. The North Barracks stuck out into the Plain towards what is now the baseball field. Ninny's quarters were located close to road in front of the West Point Club. Map by T.B. Brown, 1826. Annotations by the author.

Troublemaker Benny Roberts later in life. His highest rank was Brevet Major General (1865).

"Now Ninny knew that there were only three c1dets lo the corps that could be guilty of such a piece of impudence. But these fellows were all about the same height —and it was too dark to discover any features. Major Fowler was the commandant or cadets, and when the office hour arrived each of the three was sent for in turn to come to the commandant’s office. Ninny was then trying with all his might to see something that could enable him to say positively which was the culprit. But each one of the boys kept a countenance as serene as that of a mummy, and Ninny gave It up. I rather think that affair had something to do with his leaving the Army, which he did soon after this event. He took refuge in holy orders lo the Protestant Episcopal Church. In after years Ninny would come occasionally to officiate in the cadets’ chapel, and his appearance would always revive the old story of his foot race with Benny Roberts.

"Ninny occupied as his quarters a small building lo the eastward and about eighty yards from the old North Barracks [Note: sometimes called "Castle Harris"]. This building had previously been used for baser purposes, and some years afterwards It was used as the barber shop and boot black room, and still later it was used by Jo Simpson as an ice cream and refreshment room. It was a circular or octagonal shaped building with a cupola. Between this building and the North Barracks was a high stone wall which prevented a view of the windows of the lower floor of the barrack. Now, our worthies had transformed their brass candle sticks into small mortars, and by charging their old bell buttons they made of them miniature shells, which they could fire from the windows behind the wall, and they had struck the range so accurately that they could burst a button shell over Ninny's quarters any time. Occasionally a bombardment would commence along the whole line of windows, and Ninny's life was made so uncomfortable that he was obliged to change his quarters. But the event that immediately brought about the change was this: One morning at reveille the whole corps of cadets were astonished to see Ninny, in full tog, standing on the top of his quarters, leaning very composedly against the cupola, quietly surveying the surrounding scenery. Those who were not lo the secret of the affair suspected that he had taken his stand there in a fit or insanity. It was soon observed, however, that the figure did not move and that it was not Ninny, but at a little distance it was his vera effigies. Some one whom no fellow could find out had gotten into the quarters and stuffed a suit of uniform so cleverly that the resemblance was perfect, and placed it on the top of the building. This was too much for human nature to stand and the building had to be vacated."

Poor Ninny! I feel bad for him. Arnold got out of the Army after three years. Britton served sixteen years before becoming a state senator in Texas (Blutarski-esque). Benny Roberts served four years, got out, then entered service again. He earned the rank of Brevet Major General. Ninny's Cullum entry is here.

Primary Source: "Two Army Characters," Army and Navy Journal, September 14, 1878.

Go West Young Men! And Laundry Girls too!

In 1904, the Corps of Cadets went a long way from home...

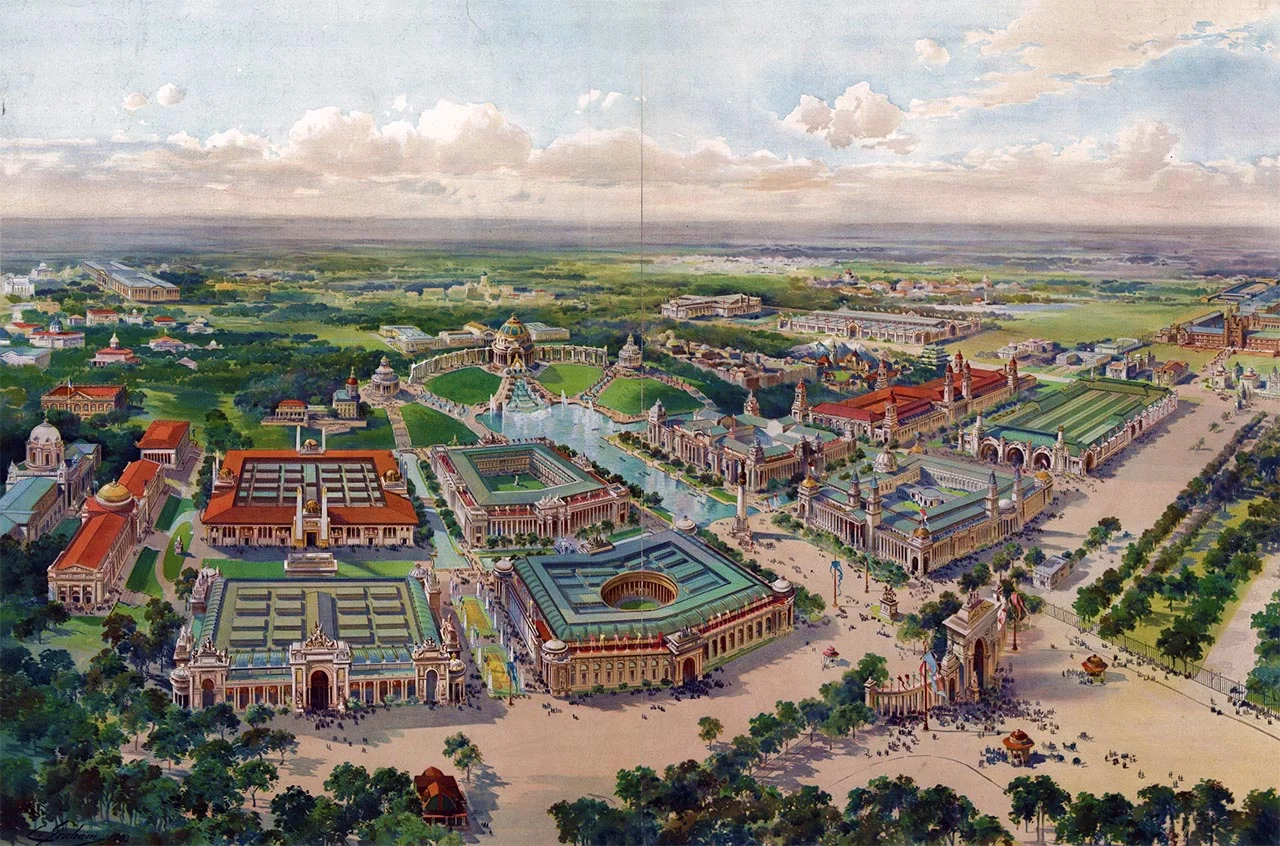

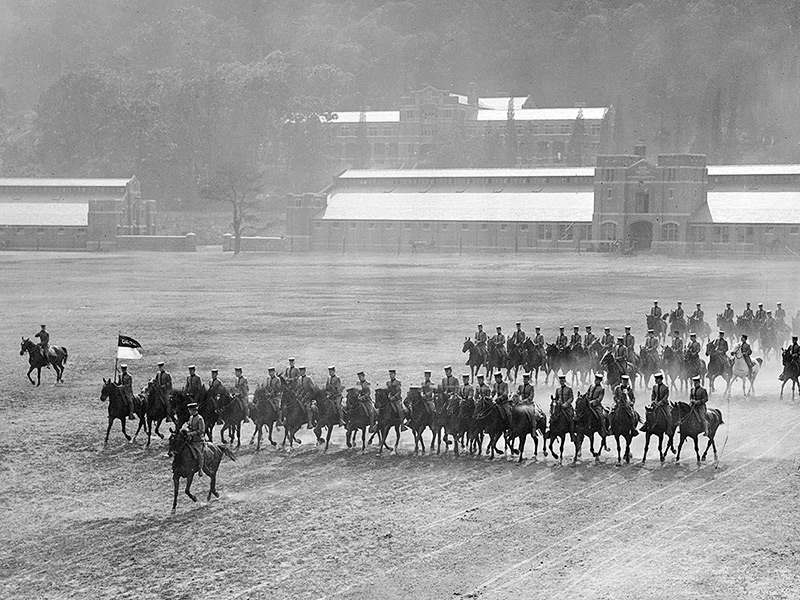

One of the most significant mass movements in West Point history has to be the trip to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, more commonly known as the St. Louis World’s Fair. In late May of 1904, just after exams but before graduation exercises, nearly the entire Corps headed westward to encamp on the Exposition’s fairgrounds for about 10 days.

This move was a logistical wonder. Four trains were chartered, leaving on two separate days. On the first day (Friday 27 May), the trains consisted of cavalry soldiers, 47 horses, 13 mules, several laundry girls, civilian employees, two mounted guns, and eleven cars full of baggage. The next day, May 28th, the trains carried 407 cadets, the Band, and officers and their wives.

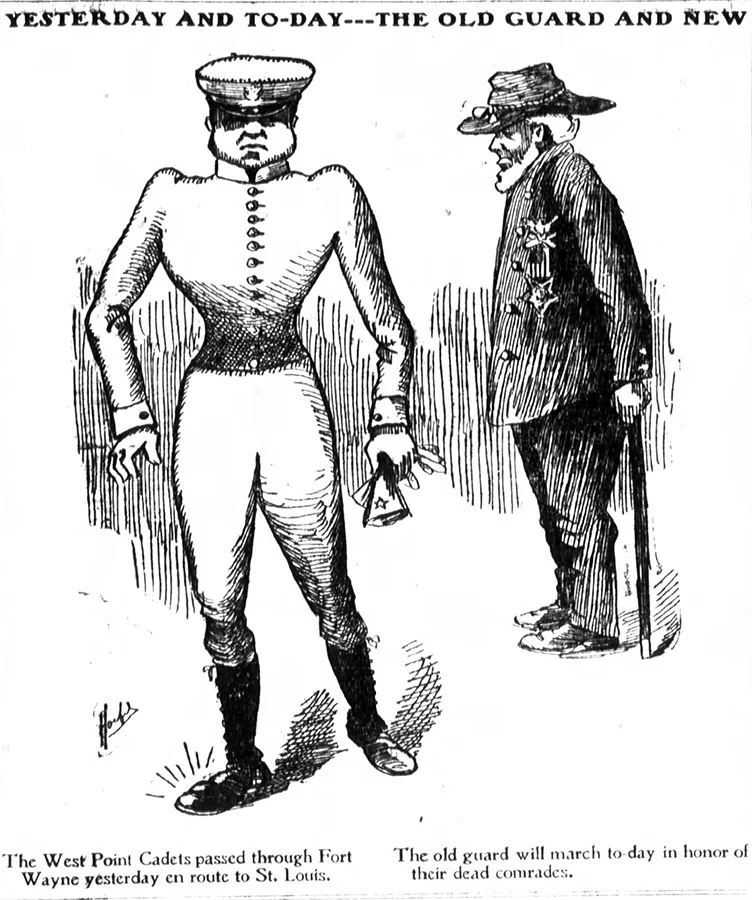

The route taken was complex. First, the trains headed to Buffalo along tracks controlled by the New York Central Railroad. Whether they went north to Albany on the west side of the River or south to Weehawken and then north from Manhattan on the New York Central’s main route is unclear. In Buffalo, the trains transferred to the Lake Shore line of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway. Despite a reported derailment on this leg (which must have been minor), this route brought the Corps as far as Toledo, where the trains transferred again to the Wabash Railroad that allowed fast transport to Decatur and on to St. Louis. Newspapers along the route in towns such as Syracuse, Fort Wayne, and Decatur reported the movement. A planned breakfast stop in Decatur was cancelled when, according to The Daily Review, the train made excellent time and was too early for breakfast.

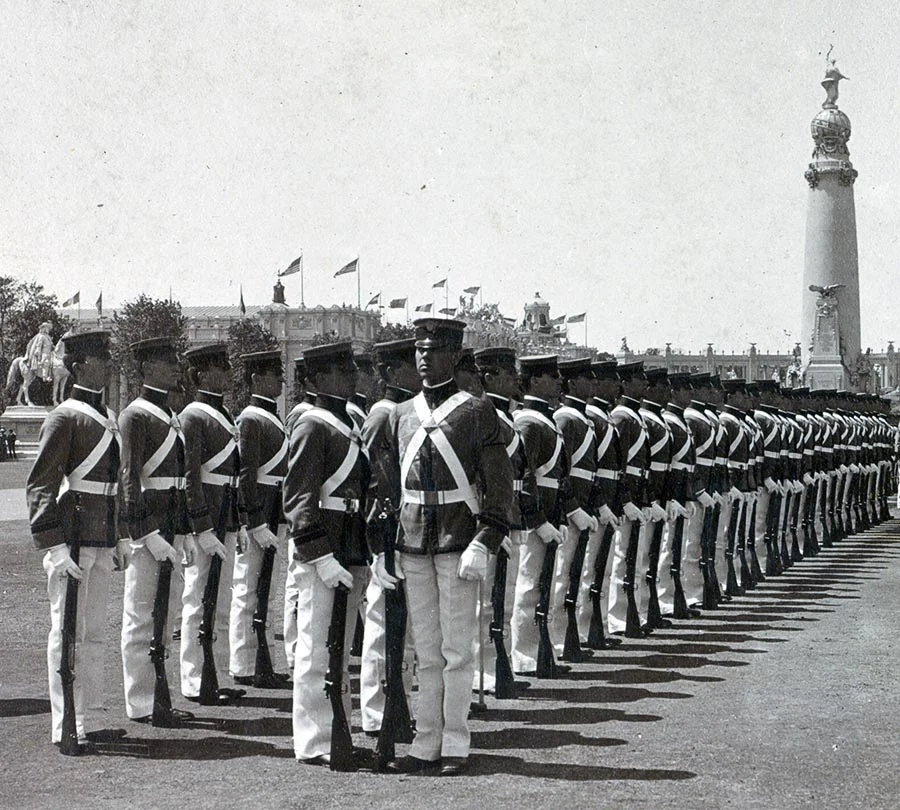

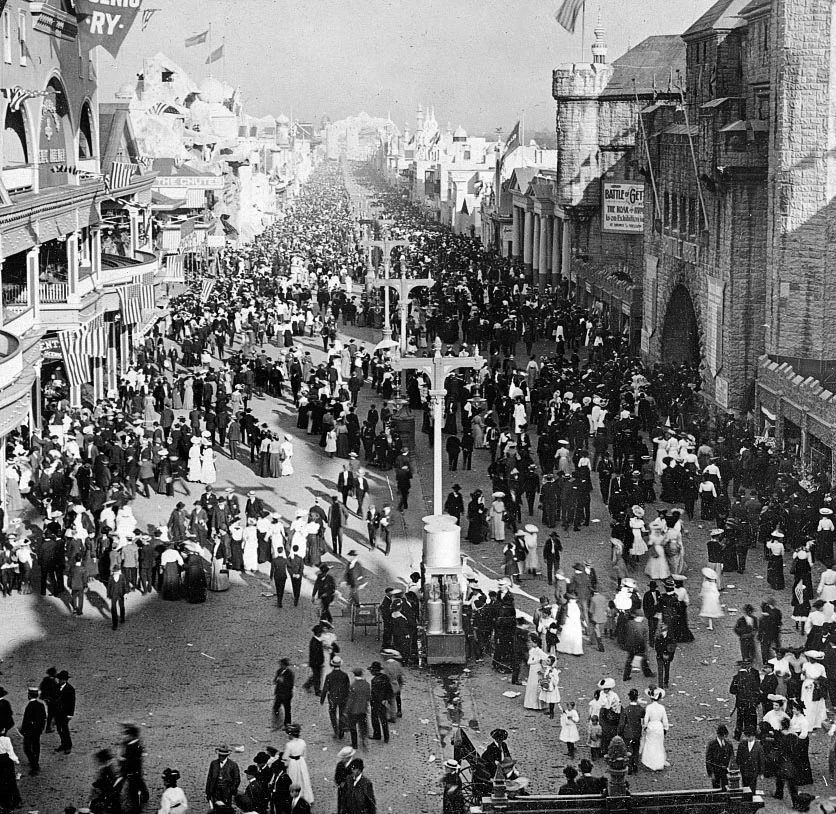

When the Corps of Cadets arrived in St. Louis on 30 May, they had to set up their encampment, although some work had been done already by enlisted soldiers. The weather was not great and the cadets had to work in mud. The Exposition was open from April to December of 1904 with certain periods of that time having themes. The Cadets were the stars of “Military Week” but shared the spotlight with other military academies and Regular Army troops. Attendance was often over 50,000 people per day. Hundreds of buildings and thousands of sculptures graced the grounds.

On their first day, a large parade was held that included hundreds of Union Civil War veterans. At the end, one paper says that “impromptu” military exercises were held. The cadets spent much of the next week parading, conducting exercises, and basically being shown off.

But, they had time for fun as well. Apparently there were no restrictions on cadet free time and they were allowed to leave the Fair as long as their destinations were approved by an officer. This was apparently necessary to prevent cadets from inviting each other to dinner and then telling their chain-of-command that they had been invited to dine somewhere. Perhaps at the Fair they enjoyed ice cream cones, hot dogs, and Dr. Pepper, all invented earlier but popularized for a national audience at the Exposition.

But not everything went as planned. First, dancing rules had to be issued. For example:

Cadets, dancing with ladies, must dance with their left arm extended and under no circumstances will they be allowed to bend the right elbow so as to draw their partner close to them.

Furthermore, social events had to be properly chaperoned. This became a problem when not enough chaperones could be found. The New York Times (9 June 1904) reported on a local newspaper account that said the following:

Inability to find, within the newly drawn circle of One Hundred fifty disengaged matrons to act as chaperons (sic) is the supposed cause of the cancellation by the Board of Lady Managers of the invitations sent out to the reception which was to have been tendered by that important body to the West Point cadets Wednesday evening.

That’s life. Sometimes you get to dance with your left arm extended and sometimes you don’t.

The Cadets returned to West Point in time for mid-June Graduation Exercises.

If you're enjoying this site, please use the buttons at the bottom to share on social media.

Select Sources:

"NO CHAPERONS, NO RECEPTION," New York Times, 9 June 1904.

"Yesterday and To-Day," The Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 30 May, 1904.

"West Point Men Charge on Mud," St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 May 1904.

"Breakfast Order was Cut Out," The Daily Review (Decatur, IL), 30 May 1904.

"The Board of Visitors — Cadets Starting for St. Louis," Poughkeepsie Eagle-News, 28 May 1904.

General Scott's Fall

General Winfield Scott's 1858 visit to West Point was memorable...

Recently on the Facebook page for this site, I wrote about the very candid news accounts concerning General Winfield Scott's gastrointestinal issues. Today, another look at the hero's health issues. And please remember to share this article to Twitter, FB, etc. by using the buttons at the bottom of the page.

General Winfield Scott, beloved military hero and failed presidential candidate, spent a great deal of time at West Point as he grew older. In September of 1858, Scott, already over 70 years old and still on active duty, was staying at Cozzens' Hotel in what is now Highland Falls. The large hotel was located close to where now stands a McDonalds. Scott's stay this time would be memorable and garner national press. According to the Louisville Daily Courier:

Gen. Scott had a very severe fall on the stairs at Cozzens' Hotel, West Point, last week... Having had a bullet through one shoulder, and a sword thrust through the other arm during his campaigns, he was unable to break the force of the fall by his arms, and his back was severely injured. He cannot move without great pain. He has been cupped and leeched, and is somewhat better, suffers intensely. At his advanced age, and with so ponderous a frame, it is a serious affair to have such a fall, and he is fortunate to escape with life.

Cupped and leeched! The reference to Scott's ponderous frame refers to the General's weight, which at this point was about 300 pounds. Fortunately, Scott recovered. The Tennessean newspaper reported the following:

General Scott has so far recovered from the effects of his recent fall that he is able to move about and transact his ordinary official and private business. Reports from Cozzens' Hotel, West Point, where hs is stopping, state that he suffered intense pain from the bruises he received, but his constitution is yet so good that he recovered in a surprisingly short time, considering his age and the severity of the accident to a man of his large frame. The old General has evidently stamina enough left to be President one term at least before he dies.

Scott retired to West Point in 1861 amidst the turmoil of politics and military disagreements of the early days of the Civil War. Although a Virginian, he remained loyal to the Union. In total, he served 53 years in the Army. Scott died in 1866 and is buried in the West Point Cemetery. I'm sure we'll explore some of his exploits in the future.

Sources:

"Accident to Gen. Scott," The Louisville Daily Courier, 27 Sep 1858, 1.

"Recovery of Gen. Scott," The Tennessean, 1 Oct 1858, 2.

Crazy First Days as a Cadet, 1814

In his first days as a West Point cadet, George D. Ramsay saw horrific things...

One of the craziest first days as a cadet has to be the experience of future Chief of Ordnance George D. Ramsay, USMA Class of 1820. Ramsay was appointed at just age 12! Setting off from Virginia in August of 1814, the young man and a chaperone made their way by stage to New York City, a journey of about four days passing through Baltimore, Lancaster, and Philadelphia. They arrived at the American Hotel on Broadway to rest before finding passage to West Point. But, because Ramsay was wearing his cadet uniform for the journey, he was recognized and informed that the Corps was actually in the City encamped on Governor's Island. After meeting a couple of cadets, he was invited to join them at the encampment and finish the journey to West Point with the Corps.

Arriving on Governor's Island, Ramsay settled into one of the cadet tents and unofficially joined the Corps' activities. Because the War of 1812 was still underway, the camp gave a real Army experience for the Corps. This was never clearer than on Ramsay's first full day in camp. The 12-year old was welcomed to the Army by witnessing the execution of a deserter. This poor soul was likely Thomas Fitzgerald, who's death on August 20, 1814 was recorded in The Long-Island Star on August 24th. They reported that Fitzgerald was "shot on Governor's Island pursuant to the sentence of a Court martial, for frequent acts of desertion." What a first day!

Ramsay's experience as a new cadet only got worse. After a sloop trip back to West Point with the Corps, the cadets all headed for the two messes, Mrs. Thompson's (near the current Firstie Club) and one operated by Isaac Partridge on the Plain near the present location of the Supe's House. Ramsay went to Mrs. Thompson's first, but was turned away. He then tried Partridge's and was also barred from entry. Homesick and forlorn, he wandered alone around the Plain until his spirits lifted. Wandering back to Mrs. Thompson's, he was shown kindness by Souverine, Mrs. Thomspon's assistant. Souverine was of African-Caribbean ancestry and was known for her wit and good-humor. With a good meal in him, Ramsay's spirits were lifted and his cadet career was off to a proper start.

Best of luck to the West Point Class of 2020!!

Sources:

Ramsay, George D. "Recollections of Cadet Life of George D. Ramsay," in George W. Cullum, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y., Third Edition Revised and Extended, Vol. III. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1891.

West Point, from above Washington Valley, 1834

A breakdown of a beautiful 1834 engraving of West Point.

From time to time I'll be annotating old art to help you better understand the past landscapes of the Hudson Valley. Today's installment is West Point, from above Washington Valley, looking down the river, a painted engraving by George Cooke (painter) and W.J. Bennett (engraver). It was published by the New York firm of Parker & Clover circa 1834. Bennett was well-known for his aquatints, a type of engraving that produces a watercolor look. Cooke likely would have painted the original scene and then Bennett would make an engraving that could be printed in quantity. The prints were then hand-colored. Bennett was a member of the National Academy of Design, founded in 1825 by artists including Hudson River School giants Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand as well as Samuel F.B. Morse (-- --- .-. ... .) . Longtime Professor of Drawing at the Academy Robert W. Weir was also a member (after 1829).

First, look at the print (and an enlargement) and then below you'll find a copy with callouts labeling the key features.

Can you identify any of the buildings? Four still exist today (not including monuments and forts). Here's an enlargement:

Ok, here are the annotated copies!

Notes:

- The hill that the people are looking from really doesn't exist anymore. It was modified and eventually level to make way for railroad tracks. It was approximately on the site of the current rugby complex at West Point.

- The South barracks were completed in 1815 along with the Academy building, and the North Barracks were completed in 1817. All three buildings were stone.

- Both the current Superintendent's and Commandant's houses are visible in this artwork, along with other houses built at the time (1819-1820) that no longer exist.

- The three brick houses on Professors' Row (only two are visible here) were all completed in the 1820s. Notice that they do not have the "wings" and porches they have now.

- Wood's Monument stood on a small hill known as Monument Hill (sometimes Bunker's Hill on older maps). The hill no longer exists, having been leveled to create the road that now goes from the Plain to the Firstie Club.

- The West Point Hotel was completed in 1829.

- The Kosciuszko Monument was dedicated in 1828.

- Notice how visible the Cadet Monument is from the River. The trio of visible monuments along with the flagpole were useful navigation ads for sloop and steamboat captains.

- Washington Valley was the site of the Red House owned during the Revolution by the Moore family. The Valley extends inland past what is now the West Point Golf Course.

You can get a free high-resolution copy of the print at the Library of Congress website here.

Lightning Strikes the Flag Pole, 1895

In honor of Flag Day (and the Army's Birthday) comes this story of resiliency from June 30, 1895:

"At 8:30 o’clock this morning the cadets who attend services in the little Catholic church at the foot of the hill assembled in the barracks area. They marched along Professor’s Row, and turned in the path through Trophy Point, where the large flagpole stands. The pole was over 100 feet high. The squad of cadets had just passed, and were not yet thirty feet from the pole, when a vivid flash of lightning came down from Cro’ Nest.

"The detachment of cadets was stunned, and a few fell to the ground, but in less than a minute all had recovered.

"Pieces of wood from three to fifteen feet long were strewn all around them. The big flagpole had been struck by the bolt, and was splintered into thousands of pieces. To-day hundreds of people are viewing the ruined pole, and nearly half of it has been carried away by relic hunters."

A new pole was promised in “a few days” but it seems that it took three months to begin erecting the replacement (mid-October). Its specifications were listed as:

Bottom Section: 97' long made of white pine, 2.5’ in diameter set into a brick-lined hole 14’ feet and filled with concrete.

Top Section: 60’

Total height: 130’

Cost: $1,000

Happy Flag Day!

Sources:

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. "View of West Point." New York Public Library Digital Collections.

"A New Flagstaff on Trophy Point," New York Times, October 19, 1895, 10.

"The West Point Flagpole Gone," New York Times, July 1, 1895, 1.

A Problematic Purchase of Polo Ponies

Polo was in fashion at West Point (and the Army) in the first decade of the 20th century. The game was being played at West Point, often with cavalry horses, at least as early as 1902-03. In 1910, a group of cadets asked the Quartermaster, Lieutenant Colonel John M. Carson, Jr., for eight well-trained horses. Carson thought this was a good idea and polled the cavalry officers assigned to the Academy. They also agreed that the ponies were a good idea and Carson went forward with a $2,000 purchase for the horses. He then sent a bill to Washington for reimbursement.

As you might have guessed, the expense was refused as the horses were not “cavalry, artillery, or engineer horses” and Carson was told he was personally responsible for the purchase. This made him the focus of much ribbing at the Academy. According to the New York Times (1910), Colonel Hugh L. Scott, Superintendent, said to Carson, “I see you own some very fine ponies.” Carson replied, “Indeed I do; at least I suppose I do, but $2,000 is a lot of money for one army officer to have to scrape up.”

What happened to the ponies in unclear, but COL Scott was confident that Carson would not, in the end, have to personally pay for the ponies. He told the Times, “He’s got eight as fine polo ponies as there is in this country. Polo ponies are needed at West Point as the game is of great value in teaching the cadets horsemanship and I am sure that in the end Carson will not have to pay the money.”

Polo ponies became a real issue in the Army budget because of the cost to maintain and move them to competitions. To read a lengthy, and sometimes funny, discussion in Congress about the purchase of polo ponies for West Point, check out the Congressional Record from 1913 here.

BONUS: One of the funniest moments in TV history:

Source: “Polo Ponies Bring Col. Carson Dismay.” New York Times, July 17, 1910.

Cadets' Monument, 1820

This hand-colored etching of the Cadet Monument (often called the "Cadets' Monument" in early writings) is by English-born artist John Rubens Smith and is thought to be from about 1820 (certainly 1819-1825).

Fun things to notice (see the infographic below):

- One of the women on the left of the Monument is sharing a gaze with the cadet leaning against the tree in the middle. The Monument was a popular attraction for West Point visitors and cadets loved any chance to mingle.

- Notice the cadets taking a shortcut and coming up the bank from the River.

- At the far right, in the background, you can see part of the yellow Long Barracks that burned down in the mid-1820s.

- Also in the background is the old dock, located at about the site of the current helipad. At the time, steamboats were still rare on the river and most boats were sloops.

Why Execution Hollow?

Welcome to ExecutionHollow.com. I've created this blog to share information about the geography and history of the Hudson Valley and West Point collected over years of personal research. But why "Execution Hollow?" Execution Hollow was a a prominent depression on the Plain at West Point and a key feature of the landscape until about 1912. This now-lost part of the terrain represents my interest in West Point history because it was a feature that was known to all but then completely disappeared. Few visitors sitting in the western stands at a West Point parade would guess that a century and a half ago, there was a deep hole at the same place. I hope that this blog will bring these forgotten aspects of the Hudson Highlands and West Point to a wider audience.

My Focus:

- West Point and the Hudson Valley BEFORE World War I.

- Fun facts, random trivia, and in-depth articles (from time-to-time).

What I will avoid and not tolerate:

- Current West Point news, issues, policy, and events, unless they directly deal with pre-WWI.

- Abusive comments, hatred, know-it-all's, and rudeness. If you don't like what I write or post, send me the link to your own blog.

The Disclaimer:

- This website and associated social media are not affiliated with the United States Military Academy, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government. Any opinions expressed are the author's own and based on the author's personal research.

If you like what you find, please use the buttons below to share on Facebook, Twitter, etc. and spread the word!